Who Invented Cinema, the Camera, or Film?

The first machine patented in the United States that showed animated pictures or movies was a device called the "wheel of life" or "zoopraxiscope". Patented in 1867 by William Lincoln, moving drawings or photographs were watched through a slit in the zoopraxiscope. However, this was a far cry from motion pictures as we know them today. Modern motion picture making began with the invention of the motion picture camera.

The first machine patented in the United States that showed animated pictures or movies was a device called the "wheel of life" or "zoopraxiscope". Patented in 1867 by William Lincoln, moving drawings or photographs were watched through a slit in the zoopraxiscope. However, this was a far cry from motion pictures as we know them today. Modern motion picture making began with the invention of the motion picture camera.

The Frenchman Louis Lumiere is often credited as inventing the first motion picture camera in 1895. But in truth, several others had made similar inventions around the same time as Lumiere. What Lumiere invented was a portable motion-picture camera, film processing unit and projector called the Cinematographe, three functions covered in one invention.

The Cinematographe made motion pictures very popular, and it could be better be said that

Lumiere's invention began the motion picture era. In 1895, Lumiere and his brother were the first

to present projected, moving, photographic, pictures to a paying audience of more that one person.

Lumiere's invention began the motion picture era. In 1895, Lumiere and his brother were the first

to present projected, moving, photographic, pictures to a paying audience of more that one person.

The Lumiere brothers were not the first to project film. In 1891, the Edison company successfully

demonstrated the Kinetoscope, which enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures.

Later in 1896, Edison showed his improved Vitascope projector and it was the first commercially,

successful, projector in the U.S..

demonstrated the Kinetoscope, which enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures.

Later in 1896, Edison showed his improved Vitascope projector and it was the first commercially,

successful, projector in the U.S..

A D V E N T U R E S in C Y B E R S O U N DThe Inventors in CinemaTo celebrate 100 years of Cinema, we look back at some of the major developments in the history of the moving image, and the inventors behind them. The Inventions before 1896 Shadow plays, involving projection using a lantern and animated puppets, date back to the 1420s in Europe, having spread from India or Java via the Middle East. Seraphin opened a shadow play theatre in Versailles in 1776 which survived the French Revolution and ran until the 1850s. The Magic Lantern is mentioned in Pepys diary in the 17th century, and by 1800 travelling showmen were using lanterns with a lens and illuminated by oil. The Fantasmagorie of the 1790s projected ghost shows from a hidden lantern onto smoke. The development of large scale entertainment soon became possible when Professor Robert Hare invented the oxy-hydrogen blowlamp in 1802; this led to Lieutenant Thomas Drummond's signal light of 1826, which used calcium oxide to produce the 'lime light'. The Thaumatrope demonstrated persistence of vision, which the Victorians thought important for perception, although we now know this to be psychological. Joseph Plateau in Belgium and then Michael Faraday in England studied persistence of vision in the 1820s and this led to the spinning slits of the Phenakistoscope invented by Plateau, and the simultaneous independent invention, in 1833, by the Austrian Simon Stampfer of an almost identical device which he named the Stroboscope. In 1867, M. Bradley (on 6th March in England) and William E. Lincoln (on 23rd April in America), filed virtually identical patents for The Zoetrope, this used 13 slots and 13 pictures spinning round in a metal cylinder: varying the number of pictures simulated relative figure movement. The device was cheaper to produce, ran more smoothly and for longer than the Phenkistoscope, and could be viewed by several people at once. A large number of devices were being developed throughout Europe and America, and by the 1880s audiences of 3000 were watching shows involving 2 or 3 lanterns dissolving in and out to produce an absorbing experience. The next step was to use sequence photography to create moving pictures, and the first successful device for sequence photography was Eadweard Muybridge, who took 12 photographs of the horse 'Abe Edgington' in 1878 and demonstrated how this represented a mere half second of motion. His Zoopraxiscope device of 1879 can be seen in the Kingston Museum, Surrey, UK. Inspired by Muybridge's work, the Frenchman Etienne-Jules Marey analysed high-speed motion and throughout the early 1890s, helped by developments such as sensitized paper superseding glass plates and general improvements in the equipment available, produced chronophotographic sequence cameras and demonstrated the principles which formed the basis of the cinematography. Edison's Kinetoscope was the first equipment to use 35mm film, but this was a single viewer machine. The designer W.K.L.Dixon worked for Edison in the USA and then in 1894 moved to England where he helped develop the Mutoscope ('What the Butler Saw') machines. The first 'movie shows' The Lumiere brothers, Auguste and Louis, produced what is arguably the first real cinema show with the presentation of their Lumiere Cinematographe to a paying audience at the Grand Cafe in Paris on 28th December 1895. In the meanwhile, Robert (R.W.) Paul, a London engineer, had seen the Kinetoscope parlour in Oxford Street and discovered that the machine had not been patented in England. He set about making copies, only to be frustrated when he tried to buy films which the suppliers would only sell to purchasers of the original machines. However, he soon met up with Birt Acres, a photographer, and together they produced a camera virtually identical to Marey's chronophotographic film camera. On 30th March 1895, Acres filmed the Oxford and Cambridge boat race, and on 29th May the same year he filmed the Derby. On 27th May, Acres patented the Kinetic camera - based on the Paul-Acres machine, and this was probably the cause of the split between the two men which arose shortly after Acres had returned from Germany where he had filmed the June opening of the Kiel canal.  The films were only viewed as a peep-show until Acres projected them, to the Royal Photographic Society on 14th January 1896, and later with his Kineopticon at Piccadilly Circus on 21st March 1896, about a month after the Lumieres' first London show. Until purpose-built cinemas began to appear around 1910, shows would be presented as a turn at the theatre or shown in converted shops. Fairground Bioscope shows toured from 1896 until the end of World War One. The film used was the 2 3/4 inch (70mm) film developed for Kodak snapshot cameras, which most early movie men split in half, although the Biograph used 70mm film to give better quality. It is often suggested that the technical qualities of the early films are superior to later black and white films, however it must be realised that as the Lumieres' father owned a photographic business they were original manufacturers, and so their lovingly made films should not be compared to a well-worn duplicate of a 30's B-movie. Sound and Colour The first films had no sound unless the pit orchestra chose to play an accompaniment or the operator devised his own sound effects or used a device such as the 'Allefex' machine. Sound produced by a gramophone playing records synchronised to the film was first demonstrated by Leon Gaumont at the Paris Exposition of 1900, but there were considerable difficulties involving speed variations and sound amplification. Gaumont continued his developing and in 1910 he demonstrated his Chronophone to the Academie des Sciences in Paris. In Germany, Oskar Meester patented several synchronisation methods in 1903, and within 10 years his Biophon system was installed in 500 German theatres. The first internationally successful method was the Vitaphone system, backed by Sam Warner of Warner Brothers, which was used in the 1927 Al Jolson film 'The Jazz Singer'. The system was based on 16 inch discs, playing at 33 1/3 rpm from the centre out, but within 3 years the costs of breakages and shipping the disks led Warner Brothers to discontinue the system. Although F. von Madelar had patented various inventions for mechanically recording sound on film in 1913, and Emil Lauste had demonstrated sound-on-film recording around the same time, their ideas were largely unexploited. The eventual system adopted in 1928 arose from an amalgamation of Lee de Forest and Theodore Case's Phonofilm system with Charles A. Hoxie's Photophone system. Subsequent developments in sound have been the Dolby system, and more recently digital sound in the forms of Dolby digital which is on the film and Digital Theatre Sound (DTS) which is on a Compact Disc that is automatically synchronised even if the film is edited. The first successful results with colour filming and projection involved the Kinemacolor system, patented in November 1906 by George Albert Smith, a Brighton film-maker. A 'full colour' image is produced by shooting alternate frames on 'black and white' film with red and green filters and then projecting the film back with appropriate filter at 32 frames per second (double speed). This produces a colour image devoid of pure blue, however modern experiments have shown the results to be effective. 3-D films come and go, but are generally disliked on the grounds that the glasses cause headaches. In reality the headaches are caused by the brain trying to compensate for misaligned images, caused by the film being either badly shot or projected: both these functions require great skill by the operator. One system in use today is the IMAX system which uses 70mm film sideways to give better quality. In the early days of cinema, no one was entirely sure of the correct way to retain copyright of their film, and as a result the Library of Congress has a collection of frame-by-frame paper prints of films up to 1912. In a neat twist to the original reason for the copy being made, there are instances where these paper prints have been re- filmed to produce a new copy of a film of which no other record remains. Thank you to the Museum of the Moving Image (MOMI) and Stephen Herbert of the British Film Institute for their help with this article. |

| The Pre-1920s Early Cinematic Origins and the Infancy of Film |

Innovations Necessary for the Advent of Cinema:

Optical toys, shadow shows, 'magic lanterns,' and visual tricks have existed for thousands of years. Many inventors, scientists, manufacturers and scientists have observed the visual phenomenon that a series of individual still pictures set into motion created the illusion of movement - a concept termed persistence of vision. This illusion of motion was first described by British physician Peter Mark Roget in 1824, and was a first step in the development of the cinema.

A number of technologies, simple optical toys and mechanical inventions related to motion and vision were developed in the early to late 19th century that were precursors to the birth of the motion picture industry:

Late 19th Century Inventions and Experiments: Muybridge, Marey, Le Prince and Eastman

Pioneering Britisher Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), an early photographer and inventor, was famous for his photographic loco-motion studies (of animals and humans) at the end of the 19th century (such as 1882's published "The Horse in Motion"). In the 1870s, Muybridge experimented with instantaneously recording the movements of a galloping horse, first at a Sacramento (California) race track. In June, 1878, he successfully conducted a 'chronophotography' experiment in Palo Alto (California) for his wealthy San Francisco benefactor, Leland Stanford, using a multiple series of cameras to record a horse's gallops - this conclusively proved that all four of the horse's feet were off the ground at the same time. Pioneering Britisher Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), an early photographer and inventor, was famous for his photographic loco-motion studies (of animals and humans) at the end of the 19th century (such as 1882's published "The Horse in Motion"). In the 1870s, Muybridge experimented with instantaneously recording the movements of a galloping horse, first at a Sacramento (California) race track. In June, 1878, he successfully conducted a 'chronophotography' experiment in Palo Alto (California) for his wealthy San Francisco benefactor, Leland Stanford, using a multiple series of cameras to record a horse's gallops - this conclusively proved that all four of the horse's feet were off the ground at the same time. Muybridge's pictures, published widely in the late 1800s, were often cut into strips and used in a Praxinoscope, a descendant of the zoetrope device, invented by Charles Emile Reynaud in 1877. The Praxinoscope was the first 'movie machine' that could project a series of images onto a screen. Muybridge's stop-action series of photographs helped lead to his own 1879 invention of the Zoopraxiscope (or "zoogyroscope", also called the "wheel of life"), a primitive motion-picture projector machine that also recreated the illusion of movement (or animation) by projecting images - rapidly displayed in succession - onto a screen from photos printed on a rotating glass disc. Muybridge's pictures, published widely in the late 1800s, were often cut into strips and used in a Praxinoscope, a descendant of the zoetrope device, invented by Charles Emile Reynaud in 1877. The Praxinoscope was the first 'movie machine' that could project a series of images onto a screen. Muybridge's stop-action series of photographs helped lead to his own 1879 invention of the Zoopraxiscope (or "zoogyroscope", also called the "wheel of life"), a primitive motion-picture projector machine that also recreated the illusion of movement (or animation) by projecting images - rapidly displayed in succession - onto a screen from photos printed on a rotating glass disc. True motion pictures, rather than eye-fooling 'animations', could only occur after the development of film (flexible and transparent celluloid) that could record split-second pictures. Some of the first experiments in this regard were conducted by Parisian innovator and physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey in the 1880s. He was also studying, experimenting, and recording bodies (most often of flying animals, such as pelicans in flight) in motion using photographic means (and French astronomer Pierre-Jules-Cesar Janssen's "revolving photographic plate" idea). True motion pictures, rather than eye-fooling 'animations', could only occur after the development of film (flexible and transparent celluloid) that could record split-second pictures. Some of the first experiments in this regard were conducted by Parisian innovator and physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey in the 1880s. He was also studying, experimenting, and recording bodies (most often of flying animals, such as pelicans in flight) in motion using photographic means (and French astronomer Pierre-Jules-Cesar Janssen's "revolving photographic plate" idea). In 1882, Marey, often claimed to be the 'inventor of cinema,' constructed a camera (or "photographic gun") that could take multiple (12) photographs per second of moving animals or humans - called chronophotography or serial photography, similar to Muybridge's work on taking multiple exposed images of running horses. [The term shooting a film was possibly derived from Marey's invention.] He was able to record multiple images of a subject's movement on the same camera plate, rather than the individual images Muybridge had produced. In 1882, Marey, often claimed to be the 'inventor of cinema,' constructed a camera (or "photographic gun") that could take multiple (12) photographs per second of moving animals or humans - called chronophotography or serial photography, similar to Muybridge's work on taking multiple exposed images of running horses. [The term shooting a film was possibly derived from Marey's invention.] He was able to record multiple images of a subject's movement on the same camera plate, rather than the individual images Muybridge had produced.

Marey's chronophotographs (multiple exposures on single glass plates and on strips of sensitized paper - celluloid film - that passed automatically through a camera of his own design) were revolutionary. He was soon able to achieve a frame rate of 30 images. Further experimentation was conducted by French-born Louis Aime Augustin Le Prince in 1888. Le Prince used long rolls of paper covered with photographic emulsion for a camera that he devised and patented. Two short fragments survive of his early motion picture film (one of which was titled Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge).

The work of Muybridge, Marey and Le Prince laid the groundwork for the development of motion picture cameras, projectors and transparent celluloid film - hence the development of cinema. American inventor George Eastman, who had first manufactured photographic dry plates in 1878, provided a more stable type of celluloid film with his concurrent developments in 1888 of sensitized paper roll photographic film (instead of glass plates) and a convenient "Kodak" small box camera (a still camera) that used the roll film. He improved upon the paper roll film with another invention in 1889 - perforated celluloid(synthetic plastic material coated with gelatin) roll-film with photographic emulsion.

The Birth of US Cinema: Thomas Edison and William K.L. Dickson

In the late 1880s, famed American inventor Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931) (and his young British assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson (1860-1935)) in his laboratories in West Orange, New Jersey, borrowed from the earlier work of Muybridge, Marey, Le Prince and Eastman. Their goal was to construct a device for recording movement on film, and another device for viewing the film. Dickson must be credited with most of the creative and innovative developments - Edison only provided the research program and his laboratories for the revolutionary work.

Although Edison is often credited with the development of early motion picture cameras and projectors, it was Dickson, in November 1890, who devised a crude, motor-powered camera that could photograph motion pictures - called a Kinetograph. This was one of the major reasons for the emergence of motion pictures in the 1890s. Edison Studios was formally known as the Edison Manufacturing Company (1894-1911), with innovations due largely to the work of Edison's assistant Dickson in the mid-1890s. Although Edison is often credited with the development of early motion picture cameras and projectors, it was Dickson, in November 1890, who devised a crude, motor-powered camera that could photograph motion pictures - called a Kinetograph. This was one of the major reasons for the emergence of motion pictures in the 1890s. Edison Studios was formally known as the Edison Manufacturing Company (1894-1911), with innovations due largely to the work of Edison's assistant Dickson in the mid-1890s.

The motor-driven camera was designed to capture movement with a synchronized shutter and sprocket system (Dickson's unique invention) that could move the film through the camera by an electric motor. The Kinetograph used film which was 35mm wide and had sprocket holes to advance the film. The sprocket system would momentarily pause the film roll before the camera's shutter to create a photographic frame (a still or photographic image). The formal introduction of the Kinetograph in October of 1892 set the standard for theatrical motion picture cameras still used today. However, moveable hand-cranked cameras soon became more popular, because the motor-driven cameras were heavy and bulky.

In 1891, Dickson also designed an early version of a movie-picture projector (an optical lantern viewing machine) based on the Zoetrope - called the Kinetoscope. In 1889 or 1890, Dickson filmed his first experimental Kinetoscope trial film, Monkeyshines No. 1, the only surviving film from the cylinder kinetoscope, and apparently thefirst motion picture ever produced on photographic film in the United States. It featured the movement of laboratory assistant Sacco Albanese, filmed with a system using tiny images that rotated around the cylinder. In 1891, Dickson also designed an early version of a movie-picture projector (an optical lantern viewing machine) based on the Zoetrope - called the Kinetoscope. In 1889 or 1890, Dickson filmed his first experimental Kinetoscope trial film, Monkeyshines No. 1, the only surviving film from the cylinder kinetoscope, and apparently thefirst motion picture ever produced on photographic film in the United States. It featured the movement of laboratory assistant Sacco Albanese, filmed with a system using tiny images that rotated around the cylinder. The first public demonstration of motion pictures in the US using the Kinetoscope occurred at the Edison Laboratories to the Federation of Women’s Clubs on May 20, 1891, with the showing ofDickson Greeting. The very short film’s subject in the test footage was William K.L. Dickson himself, bowing, smiling and ceremoniously taking off his hat. The first public demonstration of motion pictures in the US using the Kinetoscope occurred at the Edison Laboratories to the Federation of Women’s Clubs on May 20, 1891, with the showing ofDickson Greeting. The very short film’s subject in the test footage was William K.L. Dickson himself, bowing, smiling and ceremoniously taking off his hat.

On Saturday, April 14, 1894, a refined version of Edison's Kinetoscope began commercial operation. The floor-standing, box-like viewing device was basically a bulky, coin-operated, movie "peep show" cabinet for a single customer (in which the images on a continuous film loop-belt were viewed in motion as they were rotated in front of a shutter and an electric lamp-light). The Kinetoscope, the forerunner of the motion picture film projector (without sound), was finally patented on August 31, 1897 (Edison applied for the patent in 1891). The viewing device quickly became popular in carnivals, Kinetoscope parlors, amusement arcades, and sideshows for a number of years.

The world's first film production studio - or "America's first movie studio," the Black Maria, or the Kinetographic Theater (and dubbed "The Doghouse" by Edison himself), was built on the grounds of Edison's laboratories at West Orange, New Jersey, on February 1, 1893, at a cost of $637.67. It was constructed for the purpose of making film strips for the Kinetoscope. It was a black, tar-paper covered building/studio (with a retractable or hinged, flip-up roof to allow sunlight in), and built with a turntable to orient itself throughout the day to follow the natural sunlight. The world's first film production studio - or "America's first movie studio," the Black Maria, or the Kinetographic Theater (and dubbed "The Doghouse" by Edison himself), was built on the grounds of Edison's laboratories at West Orange, New Jersey, on February 1, 1893, at a cost of $637.67. It was constructed for the purpose of making film strips for the Kinetoscope. It was a black, tar-paper covered building/studio (with a retractable or hinged, flip-up roof to allow sunlight in), and built with a turntable to orient itself throughout the day to follow the natural sunlight. In early May of 1893 at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Edison conducted the world's first public demonstration of films viewed through a Kinetoscope viewer and shot using the Kinetograph in the Black Maria. The exhibited 34-second film was titled Blacksmith Scene, and showed three people pretending to be blacksmiths. In early May of 1893 at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Edison conducted the world's first public demonstration of films viewed through a Kinetoscope viewer and shot using the Kinetograph in the Black Maria. The exhibited 34-second film was titled Blacksmith Scene, and showed three people pretending to be blacksmiths. The first motion pictures made in the Black Maria were deposited for copyright by Dickson at the Library of Congress in August, 1893. In early January 1894, The Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (aka Fred Ott's Sneeze) was one of the first series of short films made by Dickson for the Kinetoscope viewer in Edison's Black Maria studio with fellow assistant Fred Ott. The short five-second film was made for publicity purposes, as a series of still photographs to accompany an article in Harper's Weekly. It was the earliest surviving, copyrighted motion picture (or "flicker") - composed of an optical record (and medium close-up) of Fred Ott, an Edison employee, sneezing comically for the camera. The first motion pictures made in the Black Maria were deposited for copyright by Dickson at the Library of Congress in August, 1893. In early January 1894, The Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (aka Fred Ott's Sneeze) was one of the first series of short films made by Dickson for the Kinetoscope viewer in Edison's Black Maria studio with fellow assistant Fred Ott. The short five-second film was made for publicity purposes, as a series of still photographs to accompany an article in Harper's Weekly. It was the earliest surviving, copyrighted motion picture (or "flicker") - composed of an optical record (and medium close-up) of Fred Ott, an Edison employee, sneezing comically for the camera.

Most of the first films shot at the Black Maria included segments of magic shows, plays, vaudeville performances (with dancers and strongmen), acts from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, various boxing matches and cockfights, and scantily-clad women. Most of the earliest moving images, however, were non-fictional, unedited, crude documentary, "home movie" views of ordinary slices of life - street scenes, the activities of police or firemen, or shots of a passing train. [Footnote: the 'Black Maria' studio appeared in Universal's comedy Abbott and Costello Meet the Keystone Cops (1955).]

In the early 1890s, Edison and Dickson also devised a prototype sound-film system called theKinetophonograph or Kinetophone - a precursor of the 1891 Kinetoscope with a cylinder-playing phonograph (and connected earphone tubes) to provide the unsynchronized sound. The projector was connected to the phonograph with a pulley system, but it didn't work very well and was difficult to synchronize. It was formally introduced in 1895, but soon proved to be unsuccessful since competitive, better synchronized devices were also beginning to appear at the time. The first known (and only surviving) film with live-recorded sound made to test the Kinetophone was the 17-second Dickson Experimental Sound Film (1894-1895). In the early 1890s, Edison and Dickson also devised a prototype sound-film system called theKinetophonograph or Kinetophone - a precursor of the 1891 Kinetoscope with a cylinder-playing phonograph (and connected earphone tubes) to provide the unsynchronized sound. The projector was connected to the phonograph with a pulley system, but it didn't work very well and was difficult to synchronize. It was formally introduced in 1895, but soon proved to be unsuccessful since competitive, better synchronized devices were also beginning to appear at the time. The first known (and only surviving) film with live-recorded sound made to test the Kinetophone was the 17-second Dickson Experimental Sound Film (1894-1895).

In mid-April 1894, the Holland Brothers opened the first Kinetoscope Parlor at 1155 Broadway in New York City and for the first time, they commercially exhibited movies, as we know them today, in their amusement arcade. Patrons paid 25 cents as the admission charge to view films in five kinetoscope machines placed in two rows. Young Griffo v. Battling Charles Barnett was the first 'movie' to be screened for a paying audience on May 20, 1895, at a storefront at 153 Broadway in NYC. The 4-minute B&W film was made by Woodville Latham and his sons Otway and Grey. The staged fight had been filmed with an Eidoloscope Camera on the roof of Madison Square Garden on May 4, 1895 between Australian boxer Albert Griffiths (Young Griffo) and Charles Barnett. Shortly thereafter, nearly 500 people became cinema's first major audience during the showings of films with titles such as Barber Shop,Blacksmiths, Cock Fight, Wrestling, and Trapeze. Edison's film studio was used to supply films for this sensational new form of entertainment. More Kinetoscope parlors soon opened in other cities (San Francisco, Atlantic City, and Chicago).

Early spectators in Kinetoscope parlors were amazed by even the most mundane moving images in very short films (between 30 and 60 seconds) - an approaching train or a parade, women dancing, dogs terrorizing rats, and twisting contortionists. In 1895, Edison exhibited hand-colored or tinted movies, including Annabelle, the Serpentine Dancer, in Atlanta, Georgia at the Cotton States Exhibition. In one of Edison's 1896 films entitled The Kiss (1896), May Irwin and John C. Rice re-enacted the final scene from the Broadway play musical The Widow Jones - it was a close-up of a kiss. Disgruntled, Dickson left Edison to form his own company in 1895, called the American Mutoscope Company (see below). [By the 1897 patent date of the Kinetoscope, both the camera (kinetograph) and the method of viewing films (kinetoscope) were on the decline with the advent of more modern screen projectors for larger audiences.] Early spectators in Kinetoscope parlors were amazed by even the most mundane moving images in very short films (between 30 and 60 seconds) - an approaching train or a parade, women dancing, dogs terrorizing rats, and twisting contortionists. In 1895, Edison exhibited hand-colored or tinted movies, including Annabelle, the Serpentine Dancer, in Atlanta, Georgia at the Cotton States Exhibition. In one of Edison's 1896 films entitled The Kiss (1896), May Irwin and John C. Rice re-enacted the final scene from the Broadway play musical The Widow Jones - it was a close-up of a kiss. Disgruntled, Dickson left Edison to form his own company in 1895, called the American Mutoscope Company (see below). [By the 1897 patent date of the Kinetoscope, both the camera (kinetograph) and the method of viewing films (kinetoscope) were on the decline with the advent of more modern screen projectors for larger audiences.]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

spectator looking through the slots 'perceived' a moving picture.

spectator looking through the slots 'perceived' a moving picture.

Throughout most of the decade, silent films were the predominant product of the film industry, having evolved from vaudevillian roots. But the films were becoming bigger (or longer), costlier, and more polished. They were being manufactured, assembly-line style, in Hollywood's 'entertainment factories,' in which production was broken down and organized into its various components (writing, costuming, makeup, directing, etc.).

Throughout most of the decade, silent films were the predominant product of the film industry, having evolved from vaudevillian roots. But the films were becoming bigger (or longer), costlier, and more polished. They were being manufactured, assembly-line style, in Hollywood's 'entertainment factories,' in which production was broken down and organized into its various components (writing, costuming, makeup, directing, etc.).

Selznick International Pictures / David O. Selznick - it was formed in 1935 and headed up by David O. Selznick (previously the head of production at RKO), the son of independent film producer Lewis J. Selznick, the founder of Selznick Pictures

Selznick International Pictures / David O. Selznick - it was formed in 1935 and headed up by David O. Selznick (previously the head of production at RKO), the son of independent film producer Lewis J. Selznick, the founder of Selznick Pictures The major film studios built luxurious 'picture palaces' that were designed for orchestras to play music to accompany projected films. The 3,300-seat Strand Theater opened in 1914 in New York City, marking the end of the nickelodeon era and the beginning of an age of the luxurious movie palaces. By 1920, there were more than 20,000 movie houses operating in the US. The largest theatre in the world (with over 6,000 seats), the Roxy Theater (dubbed "The Cathedral of the Motion Picture"), opened in New York City in 1927, with a 6,200 seat capacity. It was opened by impresario Samuel Lionel "Roxy" Rothafel at a cost of $10 million. The first feature film shown at the Roxy Theater was UA's The Love(s) of Sunya (1927) starring Gloria Swanson (she claimed that it was her personal favorite film) and John Boles. [The Roxy was finally closed in 1960.] The Roxy was unchallenged as a showplace until Radio City Music Hall opened five years later.

The major film studios built luxurious 'picture palaces' that were designed for orchestras to play music to accompany projected films. The 3,300-seat Strand Theater opened in 1914 in New York City, marking the end of the nickelodeon era and the beginning of an age of the luxurious movie palaces. By 1920, there were more than 20,000 movie houses operating in the US. The largest theatre in the world (with over 6,000 seats), the Roxy Theater (dubbed "The Cathedral of the Motion Picture"), opened in New York City in 1927, with a 6,200 seat capacity. It was opened by impresario Samuel Lionel "Roxy" Rothafel at a cost of $10 million. The first feature film shown at the Roxy Theater was UA's The Love(s) of Sunya (1927) starring Gloria Swanson (she claimed that it was her personal favorite film) and John Boles. [The Roxy was finally closed in 1960.] The Roxy was unchallenged as a showplace until Radio City Music Hall opened five years later. Impresario Sid Grauman built a number of movie palaces in the Los Angeles area in this time period:

Impresario Sid Grauman built a number of movie palaces in the Los Angeles area in this time period: Two of the biggest silent movie stars of the era were Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. America flocked to the movies to see the Queen of Hollywood, dubbed "America's Sweetheart" and the most popular star of the generation - "Our Mary" Mary Pickford. She had been a child star, and had worked at Biograph as a bit actress in 1909, and only ten years later was one of the most influential figures in Hollywood at Paramount. In 1916, she was the first star to become a millionaire.

Two of the biggest silent movie stars of the era were Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. America flocked to the movies to see the Queen of Hollywood, dubbed "America's Sweetheart" and the most popular star of the generation - "Our Mary" Mary Pickford. She had been a child star, and had worked at Biograph as a bit actress in 1909, and only ten years later was one of the most influential figures in Hollywood at Paramount. In 1916, she was the first star to become a millionaire. Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. also became an American legend after switching from light comedies and starring in a series of exciting, costumed swashbuckler and adventure/fantasy films, starting with The Mark of Zorro (1920), soon followed with his expensively-financed, lavish adventure film Robin Hood (1922) with gigantic sets (famous for the scene in which he eluded death from sword-wielding attackers by jumping off a castle balcony and sliding down a 50 ft. curtain), and the first of four versions of the classic Arabian nights tale by director Raoul Walsh, The Thief of Bagdad (1924). This magical film used state of the art, revolutionary visual effects (for its smoke-belching dragon and underwater spider, the flying horse, the famed flying carpet, and magic armies arising from the dust) and displayed legendary production design.

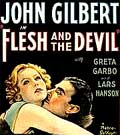

Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. also became an American legend after switching from light comedies and starring in a series of exciting, costumed swashbuckler and adventure/fantasy films, starting with The Mark of Zorro (1920), soon followed with his expensively-financed, lavish adventure film Robin Hood (1922) with gigantic sets (famous for the scene in which he eluded death from sword-wielding attackers by jumping off a castle balcony and sliding down a 50 ft. curtain), and the first of four versions of the classic Arabian nights tale by director Raoul Walsh, The Thief of Bagdad (1924). This magical film used state of the art, revolutionary visual effects (for its smoke-belching dragon and underwater spider, the flying horse, the famed flying carpet, and magic armies arising from the dust) and displayed legendary production design. Hauntingly mysterious and divine, Greta Garbo's first American film was The Torrent (1926), followed quickly by The Temptress (1926). Her first major starring vehicle was as a sultry temptress in torrid, prone love scenes with off-screen lover John Gilbert inFlesh and the Devil (1926). MGM renamed Broadway actress Lucille Le Sueur and christened her "Joan Crawford" in 1925. And Louise Brooks made her debut film in mid-decade with Street of Forgotten Men (1925). Glamorous MGM star Norma Shearer insured her future success as "The First Lady of the Screen" by marrying genius MGM production supervisor Irving Thalberg in 1927.

Hauntingly mysterious and divine, Greta Garbo's first American film was The Torrent (1926), followed quickly by The Temptress (1926). Her first major starring vehicle was as a sultry temptress in torrid, prone love scenes with off-screen lover John Gilbert inFlesh and the Devil (1926). MGM renamed Broadway actress Lucille Le Sueur and christened her "Joan Crawford" in 1925. And Louise Brooks made her debut film in mid-decade with Street of Forgotten Men (1925). Glamorous MGM star Norma Shearer insured her future success as "The First Lady of the Screen" by marrying genius MGM production supervisor Irving Thalberg in 1927. Clara Bow, a red-haired, lower-class Brooklyn girl was subjected to a major publicity campaign by B. P. Schulberg (of Preferred Pictures (1920-1926) and then Paramount's head of production in the late 20s and early 30s). He promoted his up-and-coming, vivacious future star as his own personal star, after grooming and molding her for her star-making hit film The Plastic Age (1925) as a flirtatious flapper - the "hottest Jazz Baby in Film." Bow was also exceptional inDancing Mothers (1926) and in her smash hit Mantrap (1926), and was further promoted with teaser campaigns for It (1927). She soon became known as "The It (sex appeal) Girl" (in the high-living age of flappers) after its February 1927 release. She was boosted to Paramount Studios' super-stardom in the late 1920s by more publicity campaigns, fan magazine glamorization, and rumor-spreading. Bow also starred in the epic WWI film Wings (1927), and in 1928 became the highest paid movie star (at $35,000/week). But by 1933, after years of victimizing exploitation, she had gone into serious decline and retired due to hard-drinking, exhaustion, gambling, emotional problems, a poor choice of roles, the revelation of a heavy working-class Brooklyn accent in the talkies, and a burgeoning weight problem.

Clara Bow, a red-haired, lower-class Brooklyn girl was subjected to a major publicity campaign by B. P. Schulberg (of Preferred Pictures (1920-1926) and then Paramount's head of production in the late 20s and early 30s). He promoted his up-and-coming, vivacious future star as his own personal star, after grooming and molding her for her star-making hit film The Plastic Age (1925) as a flirtatious flapper - the "hottest Jazz Baby in Film." Bow was also exceptional inDancing Mothers (1926) and in her smash hit Mantrap (1926), and was further promoted with teaser campaigns for It (1927). She soon became known as "The It (sex appeal) Girl" (in the high-living age of flappers) after its February 1927 release. She was boosted to Paramount Studios' super-stardom in the late 1920s by more publicity campaigns, fan magazine glamorization, and rumor-spreading. Bow also starred in the epic WWI film Wings (1927), and in 1928 became the highest paid movie star (at $35,000/week). But by 1933, after years of victimizing exploitation, she had gone into serious decline and retired due to hard-drinking, exhaustion, gambling, emotional problems, a poor choice of roles, the revelation of a heavy working-class Brooklyn accent in the talkies, and a burgeoning weight problem. Lon Chaney, Sr., the "man of a thousand faces," starred in the earliest version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), and then poignantly portrayed the title character of the Paris Opera House in The Phantom of the Opera (1925) in his signature role. The unveiling of the phantom's face, when Christine (Mary Philbin) rips off his mask - was (and still is) a startling sequence.

Lon Chaney, Sr., the "man of a thousand faces," starred in the earliest version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), and then poignantly portrayed the title character of the Paris Opera House in The Phantom of the Opera (1925) in his signature role. The unveiling of the phantom's face, when Christine (Mary Philbin) rips off his mask - was (and still is) a startling sequence. Another famous screen couple, dubbed "America's Lovebirds" or "America's Sweethearts" were romantic film stars Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell who were eventually paired together in twelve films. [The fact that Farrell was homosexual was kept from the public.] Their first film was Seventh Heaven (1927), a classic romantic melodrama. For their work in Seventh Heaven, Janet Gaynor received the first "Best Actress" Academy Award and director Frank Borzage received the first "Best Director" Academy Award.

Another famous screen couple, dubbed "America's Lovebirds" or "America's Sweethearts" were romantic film stars Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell who were eventually paired together in twelve films. [The fact that Farrell was homosexual was kept from the public.] Their first film was Seventh Heaven (1927), a classic romantic melodrama. For their work in Seventh Heaven, Janet Gaynor received the first "Best Actress" Academy Award and director Frank Borzage received the first "Best Director" Academy Award.

The 1930s decade (and most of the 1940s as well) has been nostalgically labeled "The Golden Age of Hollywood" (although most of the output of the decade was black-and-white). The 30s was also the decade of the sound and color revolutions and the advance of the 'talkies', and the further development of film genres (gangster films, musicals, newspaper-reporting films, historical biopics, social-realism films, lighthearted screwball comedies, westerns and horror to name a few). It was the era in which the silent period ended, with many silent film stars not making the transition to sound (e.g., Vilmy Banky, John Gilbert, and Norma Talmadge). By 1933, the economic effects of the Depression were being strongly felt, especially in decreased movie theatre attendance.

The 1930s decade (and most of the 1940s as well) has been nostalgically labeled "The Golden Age of Hollywood" (although most of the output of the decade was black-and-white). The 30s was also the decade of the sound and color revolutions and the advance of the 'talkies', and the further development of film genres (gangster films, musicals, newspaper-reporting films, historical biopics, social-realism films, lighthearted screwball comedies, westerns and horror to name a few). It was the era in which the silent period ended, with many silent film stars not making the transition to sound (e.g., Vilmy Banky, John Gilbert, and Norma Talmadge). By 1933, the economic effects of the Depression were being strongly felt, especially in decreased movie theatre attendance. As the 1930s began, there were a number of unique firsts:

As the 1930s began, there were a number of unique firsts: B-actor John Wayne made his debut in his first major role in a western directed by Raoul Walsh, The Big Trail (1930) - one of the first films shot in Grandeur, Fox's experimental wide-screen 70mm format. Both the film and the new process flopped; it would be nine more years before his star-making appearance in

B-actor John Wayne made his debut in his first major role in a western directed by Raoul Walsh, The Big Trail (1930) - one of the first films shot in Grandeur, Fox's experimental wide-screen 70mm format. Both the film and the new process flopped; it would be nine more years before his star-making appearance in  Although Austrian-born director Josef von Sternberg's best works were in his silent films (Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1928), and The Docks of New York (1929)), he acheived greatest notoriety during the 30s. Exotic German actress Marlene Dietrich's stardom was launched by von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (Germany, 1929) with her role as the leggy Lola Lola, a sensual cabaret striptease dancer and the singing of Falling in Love Again. It was Germany's first all-talking picture.

Although Austrian-born director Josef von Sternberg's best works were in his silent films (Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1928), and The Docks of New York (1929)), he acheived greatest notoriety during the 30s. Exotic German actress Marlene Dietrich's stardom was launched by von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (Germany, 1929) with her role as the leggy Lola Lola, a sensual cabaret striptease dancer and the singing of Falling in Love Again. It was Germany's first all-talking picture. Most of the early talkies were successful at the box-office, but many of them were of poor quality - dialogue-dominated play adaptations, with stilted acting (from inexperienced performers) and an unmoving camera or microphone. Screenwriters were required to place more emphasis on characters in their scripts, and title-card writers became unemployed. The first musicals were only literal transcriptions of Broadway shows taken to the screen. Nonetheless, a tremendous variety of films were produced with a wit, style, skill, and elegance that has never been equalled - before or since.

Most of the early talkies were successful at the box-office, but many of them were of poor quality - dialogue-dominated play adaptations, with stilted acting (from inexperienced performers) and an unmoving camera or microphone. Screenwriters were required to place more emphasis on characters in their scripts, and title-card writers became unemployed. The first musicals were only literal transcriptions of Broadway shows taken to the screen. Nonetheless, a tremendous variety of films were produced with a wit, style, skill, and elegance that has never been equalled - before or since. Also, in the first filming of the Ben Hecht-MacArthur play, Lewis Milestone's The Front Page (1931), a mobile camera was combined with inventive, rapid-fire dialogue and quick-editing. Other 1931 films in the emerging 'newspaper' genre included Mervyn LeRoy's social issues film about the tabloid press entitled Five Star Final (1931) (with Edward G. Robinson and Boris Karloff in a rare, non-monster role), Frank Capra's Platinum Blonde (1931) (with Jean Harlow), and John Cromwell's Scandal Sheet (1931).

Also, in the first filming of the Ben Hecht-MacArthur play, Lewis Milestone's The Front Page (1931), a mobile camera was combined with inventive, rapid-fire dialogue and quick-editing. Other 1931 films in the emerging 'newspaper' genre included Mervyn LeRoy's social issues film about the tabloid press entitled Five Star Final (1931) (with Edward G. Robinson and Boris Karloff in a rare, non-monster role), Frank Capra's Platinum Blonde (1931) (with Jean Harlow), and John Cromwell's Scandal Sheet (1931). One of the first 'color' films was Thomas Edison's hand-tinted short Annabell's Butterfly Dance. Two-color (red and green) feature films were the first color films produced, including the first two-color feature film The Toll of the Sea, and then better-known films such as Stage Struck (1925) and The Black Pirate (1926). It would take the development of a new three-color camera, in 1932, to usher in true full-color Technicolor.

One of the first 'color' films was Thomas Edison's hand-tinted short Annabell's Butterfly Dance. Two-color (red and green) feature films were the first color films produced, including the first two-color feature film The Toll of the Sea, and then better-known films such as Stage Struck (1925) and The Black Pirate (1926). It would take the development of a new three-color camera, in 1932, to usher in true full-color Technicolor. Hollywood's first full-length feature film photographed entirely in three-strip Technicolor was Rouben Mamoulian's Becky Sharp (1935) - an adaptation of English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray's Napoleonic-era novel Vanity Fair. The first musical in full-color Technicolor was Dancing Pirate (1936). And the first outdoor drama filmed in full-color was The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936).

Hollywood's first full-length feature film photographed entirely in three-strip Technicolor was Rouben Mamoulian's Becky Sharp (1935) - an adaptation of English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray's Napoleonic-era novel Vanity Fair. The first musical in full-color Technicolor was Dancing Pirate (1936). And the first outdoor drama filmed in full-color was The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936).

Hollywood Canteen (1944), the West Coast's answer to Broadway's Stage Door Canteen (1943), was typical of star-studded, plotless, patriotic extravaganzas, one of several during the war years which featured big stars who entertained the troops. [Originally, the Hollywood Canteen was a nightclub for off-duty servicemen, founded in 1942 by movie stars Bette Davis, John Garfield, and others. It provided free meals and entertainment, and was located at 1451 Cahuenga Boulevard, off Sunset Boulevard.] Big name stars and directors either enlisted, performed before soldiers at military bases, or in other ways contributed to the war mobilization. Many of the leading stars and directors in motion pictures joined the service or were called to duty - Clark Gable, James Stewart, William Wyler, and Frank Capra to name a few, and male actors were definitely in short supply. Rationing, blackouts, shortages and other wartime restrictions also had their effects on US film-makers, who were forced to cut back on set construction and on-location shoots.

Hollywood Canteen (1944), the West Coast's answer to Broadway's Stage Door Canteen (1943), was typical of star-studded, plotless, patriotic extravaganzas, one of several during the war years which featured big stars who entertained the troops. [Originally, the Hollywood Canteen was a nightclub for off-duty servicemen, founded in 1942 by movie stars Bette Davis, John Garfield, and others. It provided free meals and entertainment, and was located at 1451 Cahuenga Boulevard, off Sunset Boulevard.] Big name stars and directors either enlisted, performed before soldiers at military bases, or in other ways contributed to the war mobilization. Many of the leading stars and directors in motion pictures joined the service or were called to duty - Clark Gable, James Stewart, William Wyler, and Frank Capra to name a few, and male actors were definitely in short supply. Rationing, blackouts, shortages and other wartime restrictions also had their effects on US film-makers, who were forced to cut back on set construction and on-location shoots. A new breed of stars that arose during the war years included Van Johnson, Alan Ladd, and gorgeous GI pin-up queens Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth. (Betty Grable had signed with 20th Century Fox in 1940 and would soon became a major star of their musicals in the 1940s.) Some of Hollywood's best directors, John Ford, Frank Capra, John Huston and William Wyler, made Signal Corps documentaries or training films to aid the war effort, such as Frank Capra'sWhy We Fight (1942-1945) documentary series (the first film in the series, Prelude to War was released in 1943), Ford'sDecember 7th: The Movie (1991) (finally released after being banned by the US government for 50 years) and the first popular documentary of the war titled The Battle of Midway (1942), Huston's documentaries Report From the Aleutians (1943) and The Battle of San Pietro (1945), and Wyler's sobering Air Force documentary Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944).

A new breed of stars that arose during the war years included Van Johnson, Alan Ladd, and gorgeous GI pin-up queens Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth. (Betty Grable had signed with 20th Century Fox in 1940 and would soon became a major star of their musicals in the 1940s.) Some of Hollywood's best directors, John Ford, Frank Capra, John Huston and William Wyler, made Signal Corps documentaries or training films to aid the war effort, such as Frank Capra'sWhy We Fight (1942-1945) documentary series (the first film in the series, Prelude to War was released in 1943), Ford'sDecember 7th: The Movie (1991) (finally released after being banned by the US government for 50 years) and the first popular documentary of the war titled The Battle of Midway (1942), Huston's documentaries Report From the Aleutians (1943) and The Battle of San Pietro (1945), and Wyler's sobering Air Force documentary Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944). The most subtle of all wartime propaganda films was the romantic story of self-sacrifice and heroicism in Michael Curtiz' archetypal 40s studio film

The most subtle of all wartime propaganda films was the romantic story of self-sacrifice and heroicism in Michael Curtiz' archetypal 40s studio film  A variety of war-time films, with a wide range of subjects and tones, presented both the flag-waving heroics and action of the war as well as the realistic, every-day boredom and brutal misery of the experience: Dive Bomber (1941), A Yank in the R.A.F. (1941), Wake Island (1942), Guadalcanal Diary (1943), Bataan (1943), Winged Victory (1944), and Objective, Burma! (1945). Warner Bros.'Sergeant York (1941), directed by Howard Hawks, was typical of Hollywood offerings about the military - the story of a pacifist backwoods farmboy (Best Actor-winning Gary Cooper) who became the greatest US hero of World War I by single-handedly killing 25 and capturing 132 of the enemy. Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944) (featuring a US bomber named Ruptured Duck) starred Spencer Tracy as Lieut. Col. James Doolittle who carried out the first US bombing raid on Japan.

A variety of war-time films, with a wide range of subjects and tones, presented both the flag-waving heroics and action of the war as well as the realistic, every-day boredom and brutal misery of the experience: Dive Bomber (1941), A Yank in the R.A.F. (1941), Wake Island (1942), Guadalcanal Diary (1943), Bataan (1943), Winged Victory (1944), and Objective, Burma! (1945). Warner Bros.'Sergeant York (1941), directed by Howard Hawks, was typical of Hollywood offerings about the military - the story of a pacifist backwoods farmboy (Best Actor-winning Gary Cooper) who became the greatest US hero of World War I by single-handedly killing 25 and capturing 132 of the enemy. Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944) (featuring a US bomber named Ruptured Duck) starred Spencer Tracy as Lieut. Col. James Doolittle who carried out the first US bombing raid on Japan.

The 50s decade was known for many things: post-war affluence and increased choice of leisure time activities, conformity, the Korean War, middle-class values, the rise of modern jazz, the rise of 'fast food' restaurants and drive-ins (Jack in the Box - founded in 1951; McDonalds - first franchised in 1955 in Des Plaines, IL; and A&W Root Beer Company - formed in 1950, although it had already established over 450 drive-ins throughout the country), a baby boom, the all-electric home as the ideal, white racist terrorism in the South, the advent of television and TV dinners, abstract art, the first credit card (Diners Club, in 1951), the rise of drive-in theaters to a peak number in the late 50s with over 4,000 outdoor screens (where young teenaged couples could find privacy in their hot-rods), and a youth reaction to middle-aged cinema. Older viewers were prone to stay at home and watch television (about 10.5 million US homes had a TV set in 1950).

The 50s decade was known for many things: post-war affluence and increased choice of leisure time activities, conformity, the Korean War, middle-class values, the rise of modern jazz, the rise of 'fast food' restaurants and drive-ins (Jack in the Box - founded in 1951; McDonalds - first franchised in 1955 in Des Plaines, IL; and A&W Root Beer Company - formed in 1950, although it had already established over 450 drive-ins throughout the country), a baby boom, the all-electric home as the ideal, white racist terrorism in the South, the advent of television and TV dinners, abstract art, the first credit card (Diners Club, in 1951), the rise of drive-in theaters to a peak number in the late 50s with over 4,000 outdoor screens (where young teenaged couples could find privacy in their hot-rods), and a youth reaction to middle-aged cinema. Older viewers were prone to stay at home and watch television (about 10.5 million US homes had a TV set in 1950). In the period following WWII when most of the films were idealized with conventional portrayals of men and women, young people wanted new and exciting symbols of rebellion. Hollywood responded to audience demands - the late 1940s and 1950s saw the rise of the anti-hero - with stars like newcomers James Dean, Paul Newman (who debuted in the costume epic The Silver Chalice (1954)) and Marlon Brando, replacing more proper actors like Tyrone Power, Van Johnson, and Robert Taylor. [In later decades, this new generation of method actors would be followed by Robert DeNiro, Jack Nicholson, and Al Pacino.] Sexy anti-heroines included Ava Gardner, Kim Novak, and Marilyn Monroe - an exciting, vibrant, sexy star.

In the period following WWII when most of the films were idealized with conventional portrayals of men and women, young people wanted new and exciting symbols of rebellion. Hollywood responded to audience demands - the late 1940s and 1950s saw the rise of the anti-hero - with stars like newcomers James Dean, Paul Newman (who debuted in the costume epic The Silver Chalice (1954)) and Marlon Brando, replacing more proper actors like Tyrone Power, Van Johnson, and Robert Taylor. [In later decades, this new generation of method actors would be followed by Robert DeNiro, Jack Nicholson, and Al Pacino.] Sexy anti-heroines included Ava Gardner, Kim Novak, and Marilyn Monroe - an exciting, vibrant, sexy star. Bandstand first began as a local program for teens on WFIL-TV (now WPVI), Channel 6 in Philadelphia in early October, 1952. In mid-1956, the new host chosen for ABC-TV's American Bandstand was 26 year-old Dick Clark. By the time the show was first aired nationally, in mid-1957, it had became a mainstay for rock group performances.

Bandstand first began as a local program for teens on WFIL-TV (now WPVI), Channel 6 in Philadelphia in early October, 1952. In mid-1956, the new host chosen for ABC-TV's American Bandstand was 26 year-old Dick Clark. By the time the show was first aired nationally, in mid-1957, it had became a mainstay for rock group performances. Hollywood soon realized that the affluent teenage population could be exploited, now more rebellious than happy-go-lucky - as they had been previously portrayed in films (such as the Andy Hardy character played by Mickey Rooney). The influence of rock 'n' roll surfaced in Richard Brooks' box-office success, Blackboard Jungle (1955). It was the first major Hollywood film to use R&R on its soundtrack - the music in the credits was provided by Bill Haley and His Comets - their musical hit "Rock Around the Clock." The film also starred Glenn Ford as a war veteran and clean-cut All-American novice teacher at inner city North Manual HS (New York), where the students, led by a disrespectful, sneering punk (Vic Morrow), test his tolerance. [One of the other persuasive youths was a young Sidney Poitier.]

Hollywood soon realized that the affluent teenage population could be exploited, now more rebellious than happy-go-lucky - as they had been previously portrayed in films (such as the Andy Hardy character played by Mickey Rooney). The influence of rock 'n' roll surfaced in Richard Brooks' box-office success, Blackboard Jungle (1955). It was the first major Hollywood film to use R&R on its soundtrack - the music in the credits was provided by Bill Haley and His Comets - their musical hit "Rock Around the Clock." The film also starred Glenn Ford as a war veteran and clean-cut All-American novice teacher at inner city North Manual HS (New York), where the students, led by a disrespectful, sneering punk (Vic Morrow), test his tolerance. [One of the other persuasive youths was a young Sidney Poitier.] 1. Marlon Brando: A Symbol of Adolescent, Anti-Authoritarian Rebellion

1. Marlon Brando: A Symbol of Adolescent, Anti-Authoritarian Rebellion

The anguished, introspective teen James Dean (1932-1955) was the epitome of adolescent pain. Dean appeared in only three films before his untimely death in the fall of 1955. His first starring role was in Elia Kazan's adaptation of John Steinbeck's novel

The anguished, introspective teen James Dean (1932-1955) was the epitome of adolescent pain. Dean appeared in only three films before his untimely death in the fall of 1955. His first starring role was in Elia Kazan's adaptation of John Steinbeck's novel  Elvis' first record was That's All Right Mama, cut in July, 1954 in Memphis and released on the Sun Records label. At the time of his first hit song Heartbreak Hotel, singer Elvis Presley made his first national TV appearance in January 1956 on CBS'Tommy (and Jimmy) Dorsey's Stage Show, although he is best remembered for his controversial, sexy, mid-1956 performance of Hound Dog on the Milton Berle Show, and for three rock 'n roll performances on the Ed Sullivan Show from September 1956 to January 1957 - his last show was censored by being filmed from the 'waist-up'.

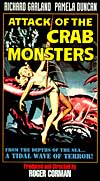

Elvis' first record was That's All Right Mama, cut in July, 1954 in Memphis and released on the Sun Records label. At the time of his first hit song Heartbreak Hotel, singer Elvis Presley made his first national TV appearance in January 1956 on CBS'Tommy (and Jimmy) Dorsey's Stage Show, although he is best remembered for his controversial, sexy, mid-1956 performance of Hound Dog on the Milton Berle Show, and for three rock 'n roll performances on the Ed Sullivan Show from September 1956 to January 1957 - his last show was censored by being filmed from the 'waist-up'. Young people attended outdoor drive-ins that showed exploitative, cheap fare created especially for them in a newly-established teen/drive-in genre. Producer/director Roger Corman (the 'B-movie King'), known for feeding low-budget, short, sci-fi/horror quickies to drive-in theatres and other neighborhood venues in the late 50s, generated films such as:

Young people attended outdoor drive-ins that showed exploitative, cheap fare created especially for them in a newly-established teen/drive-in genre. Producer/director Roger Corman (the 'B-movie King'), known for feeding low-budget, short, sci-fi/horror quickies to drive-in theatres and other neighborhood venues in the late 50s, generated films such as: Film attendance declined precipitously as free TV viewing (and the increase in popularity of foreign-language films) made inroads into the entertainment business. In 1951, NBC became America's first nationwide TV network, and in just a few years, 50% of US homes had at least one TV set. In March of 1953, the Academy Awards were televised for the first time by NBC - and the broadcast received the largest single audience in network TV's five-year history. By 1954, NBC's Tonight Show was becoming one of the most popular late-night TV shows.

Film attendance declined precipitously as free TV viewing (and the increase in popularity of foreign-language films) made inroads into the entertainment business. In 1951, NBC became America's first nationwide TV network, and in just a few years, 50% of US homes had at least one TV set. In March of 1953, the Academy Awards were televised for the first time by NBC - and the broadcast received the largest single audience in network TV's five-year history. By 1954, NBC's Tonight Show was becoming one of the most popular late-night TV shows. With a steep decline in weekly theatre attendance, studios were forced to find creative ways to make money from television - converted Hollywood studios were beginning to produce more hours of film for TV than for feature films. [In mid-decade, the average film budget was less than one million dollars.] And by mid-decade, the major studios began selling to television their film rights to their pre-1948 films for broadcast and viewing. The first feature film to be broadcast on US television (on November 3, 1956), during prime-time, was

With a steep decline in weekly theatre attendance, studios were forced to find creative ways to make money from television - converted Hollywood studios were beginning to produce more hours of film for TV than for feature films. [In mid-decade, the average film budget was less than one million dollars.] And by mid-decade, the major studios began selling to television their film rights to their pre-1948 films for broadcast and viewing. The first feature film to be broadcast on US television (on November 3, 1956), during prime-time, was  In 1956, the studios lifted the ban against film stars making TV appearances. Fast-talking, cigar-smoking, and quick-witted Groucho Marx (of the famed Marx Brothers) brought his popular radio show You Bet Your Life to television (NBC) as a game show in 1950, with a duck that would descend with $100 if one said the secret word. It lasted until 1961 - its theme music "Hooray for Captain Spaulding" was taken from the Marx Bros.' second film

In 1956, the studios lifted the ban against film stars making TV appearances. Fast-talking, cigar-smoking, and quick-witted Groucho Marx (of the famed Marx Brothers) brought his popular radio show You Bet Your Life to television (NBC) as a game show in 1950, with a duck that would descend with $100 if one said the secret word. It lasted until 1961 - its theme music "Hooray for Captain Spaulding" was taken from the Marx Bros.' second film  Because of the emergence of television as a major entertainment medium, many studios converted their sound stages for use in television production. Because labor was cheaper abroad, many producers were taking their film production overseas.

Because of the emergence of television as a major entertainment medium, many studios converted their sound stages for use in television production. Because labor was cheaper abroad, many producers were taking their film production overseas. Because television (a small black and white screen) had become affordable and a permanent fixture in most people's homes, the movies also fought back with gimmicks - color films, bigger screens, and 3-D. Bigger and more colorful films and screens, and big scale, profitable box-office epics, such as Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah (1949), the popular Biblical story starring long-haired

Because television (a small black and white screen) had become affordable and a permanent fixture in most people's homes, the movies also fought back with gimmicks - color films, bigger screens, and 3-D. Bigger and more colorful films and screens, and big scale, profitable box-office epics, such as Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah (1949), the popular Biblical story starring long-haired  and virile Victor Mature and the beautifully-bewitching Hedy Lamarr with exposed belly-button, and MGM's expensive romantic adventure King Solomon's Mines (1950), filmed on location in Africa, were designed to lure movie-goers back into the theatres. By the mid-50s, more than half of Hollywood's productions were made in color to take Americans away from their B/W TV sets.

and virile Victor Mature and the beautifully-bewitching Hedy Lamarr with exposed belly-button, and MGM's expensive romantic adventure King Solomon's Mines (1950), filmed on location in Africa, were designed to lure movie-goers back into the theatres. By the mid-50s, more than half of Hollywood's productions were made in color to take Americans away from their B/W TV sets.

With movie audiences declining due to the dominance of television, major American film companies began to diversify with other forms of entertainment: records, publishing, TV movies and the production of TV series. For example:

With movie audiences declining due to the dominance of television, major American film companies began to diversify with other forms of entertainment: records, publishing, TV movies and the production of TV series. For example: To aid the tourist industry and create another attraction, in 1960, the Hollywood Chamber of Congress inaugurated the Hollywood Walk of Fame (bronzed stars in pink terrazzo and surrounded by charcoal terrazzo squares that were embedded in the sidewalks along sections of Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street). The first star, placed on February 9, 1960, was for Joanne Woodward. However, by the mid-70s, Hollywood was better known for its adult bookstores, prostitutes, and run-down look.

To aid the tourist industry and create another attraction, in 1960, the Hollywood Chamber of Congress inaugurated the Hollywood Walk of Fame (bronzed stars in pink terrazzo and surrounded by charcoal terrazzo squares that were embedded in the sidewalks along sections of Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street). The first star, placed on February 9, 1960, was for Joanne Woodward. However, by the mid-70s, Hollywood was better known for its adult bookstores, prostitutes, and run-down look. The much-heralded Joseph L. Mankiewicz film Cleopatra (1963), filmed on location in Rome, brought together the explosive pairing of Elizabeth Taylor as the Queen of Egypt and future husband Richard Burton as Marc Antony, who brought more headlines with their blossoming romance than the budget problems. It proved to be a tremendous financial disaster for 20th Century Fox, headed by Darryl Zanuck. Taylor, already the highest-paid performer in the history of Hollywood at $1 million, had a costume wardrobe budgeted at almost $200,000, and with numerous cost over-runs, extravagant sets and thousands of costumes for the cast, the film was the most expensive up to that time at a record $44 million (in adjusted dollars, about $300 million), from an initial budget of $2 million. It was also the longest, commercially-made American film released in the US - at 4 hours and 3 minutes. [Fox was saved from financial disaster only by the release of the fact-based war epic The Longest Day (1963), an all-star re-creation of the events surrounding D-Day, and the blow was also softened by the unexpected success of

The much-heralded Joseph L. Mankiewicz film Cleopatra (1963), filmed on location in Rome, brought together the explosive pairing of Elizabeth Taylor as the Queen of Egypt and future husband Richard Burton as Marc Antony, who brought more headlines with their blossoming romance than the budget problems. It proved to be a tremendous financial disaster for 20th Century Fox, headed by Darryl Zanuck. Taylor, already the highest-paid performer in the history of Hollywood at $1 million, had a costume wardrobe budgeted at almost $200,000, and with numerous cost over-runs, extravagant sets and thousands of costumes for the cast, the film was the most expensive up to that time at a record $44 million (in adjusted dollars, about $300 million), from an initial budget of $2 million. It was also the longest, commercially-made American film released in the US - at 4 hours and 3 minutes. [Fox was saved from financial disaster only by the release of the fact-based war epic The Longest Day (1963), an all-star re-creation of the events surrounding D-Day, and the blow was also softened by the unexpected success of  With the high cost of producing and making films in Hollywood and the shrinking of studio size, many studios decreased their internal production and increased moviemaking outside the country, mostly in Britain (an economically advantageous production base), making big-budget, big-picture films there. In 1962, for example, the number of Hollywood films in production had hit an all-time low, dropping off 26% from the previous year. Two examples of films made elsewhere included these magnificent historical dramas of 12th century England:

With the high cost of producing and making films in Hollywood and the shrinking of studio size, many studios decreased their internal production and increased moviemaking outside the country, mostly in Britain (an economically advantageous production base), making big-budget, big-picture films there. In 1962, for example, the number of Hollywood films in production had hit an all-time low, dropping off 26% from the previous year. Two examples of films made elsewhere included these magnificent historical dramas of 12th century England: The major studios increasingly became financiers and distributors of foreign-made films. Two of director David Lean's 60's films, the ones that defined his career's reputation, were made in Britain. The scenic beauty and backdrops of both films became a tangible character, and opened the door for similar epic-travelogues:

The major studios increasingly became financiers and distributors of foreign-made films. Two of director David Lean's 60's films, the ones that defined his career's reputation, were made in Britain. The scenic beauty and backdrops of both films became a tangible character, and opened the door for similar epic-travelogues:

The "so-called" Renaissance of Hollywood was built upon perfecting some of the traditional film genres of Hollywood's successful past - with bigger, block-buster dimensions. Oftentimes, studios would invest heavily in only a handful of bankrolled films, hoping that one or two would succeed profitably. In the 70s, the once-powerful MGM Studios sold off many of its assets, abandoned the film-making business, and diversified into other areas (mostly hotels and casinos).

The "so-called" Renaissance of Hollywood was built upon perfecting some of the traditional film genres of Hollywood's successful past - with bigger, block-buster dimensions. Oftentimes, studios would invest heavily in only a handful of bankrolled films, hoping that one or two would succeed profitably. In the 70s, the once-powerful MGM Studios sold off many of its assets, abandoned the film-making business, and diversified into other areas (mostly hotels and casinos). multi-plex theaters - the proliferation of multi-screen chain theaters in suburban areas, replacing big movie palaces, meant that more movies could be shown to smaller audiences; the world's largest cineplex (with 18 theaters) opened in Toronto in 1979

multi-plex theaters - the proliferation of multi-screen chain theaters in suburban areas, replacing big movie palaces, meant that more movies could be shown to smaller audiences; the world's largest cineplex (with 18 theaters) opened in Toronto in 1979 in 1972, the AVCO CartriVision system was the first videocassette recorder to have pre-recorded tapes of popular movies (from Columbia Pictures) for sale and rental -- three years before Sony's Betamax system emerged into the market. However, the company went out of business a year later

in 1972, the AVCO CartriVision system was the first videocassette recorder to have pre-recorded tapes of popular movies (from Columbia Pictures) for sale and rental -- three years before Sony's Betamax system emerged into the market. However, the company went out of business a year later For example, the decade's popular independent hit and Best Picture winner, director John Avildsen's sports film

For example, the decade's popular independent hit and Best Picture winner, director John Avildsen's sports film  This low-budget, exploitative, and successful film company, founded in the mid-50s (and first named American Releasing Corporation), was largely responsible for the wave of independently-produced films of varying qualities that lasted into the decade of the 70s. The studio's executive producers were James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff, while its most notable and successful film producer was Roger Corman. He was one of the most influential film-makers of the 50s and 60s (he was dubbed the "King of the Drive-In and B-Movie") for his production of a crop of low-budget exploitation films at the time.

This low-budget, exploitative, and successful film company, founded in the mid-50s (and first named American Releasing Corporation), was largely responsible for the wave of independently-produced films of varying qualities that lasted into the decade of the 70s. The studio's executive producers were James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff, while its most notable and successful film producer was Roger Corman. He was one of the most influential film-makers of the 50s and 60s (he was dubbed the "King of the Drive-In and B-Movie") for his production of a crop of low-budget exploitation films at the time. With more power now in the hands of producers, directors, and actors, new directors emerged, many of whom had been specifically and formally trained in film-making courses/departments at universities such as UCLA, USC, and NYU, or trained in television. Corman supported this new breed of youthful maverick directors, referred to by some as "Movie Brats" or "Geeks." The AIP studio (and Corman himself) was responsible for giving a start and apprenticeship experience to many upcoming filmmaking cineastes and actors, emphasizing low-budget film-making techniques and exploitative elements.

With more power now in the hands of producers, directors, and actors, new directors emerged, many of whom had been specifically and formally trained in film-making courses/departments at universities such as UCLA, USC, and NYU, or trained in television. Corman supported this new breed of youthful maverick directors, referred to by some as "Movie Brats" or "Geeks." The AIP studio (and Corman himself) was responsible for giving a start and apprenticeship experience to many upcoming filmmaking cineastes and actors, emphasizing low-budget film-making techniques and exploitative elements.

USC graduate George Lucas added his name to the list of new directors. His first film, produced by American Zoetrope and executive-produced by Francis Coppola, was a full-length version of a student science-fiction film he had made earlier - the nightmarish vision of a dehumanized future in THX 1138 (1971). The numerical moniker would appear as an 'in-joke' in later Lucas works: as the license plate of John Milner's car in