“Oh, when shall I see that noble lady’s flawless face, with its raised nose, white teeth, pristine smile, eyes like lotus petals, and which resembles the lord of stars, the bright moon?” (Hanuman, Valmiki Ramayana, Sundara Kand, 13.68) “Oh, when shall I see that noble lady’s flawless face, with its raised nose, white teeth, pristine smile, eyes like lotus petals, and which resembles the lord of stars, the bright moon?” (Hanuman, Valmiki Ramayana, Sundara Kand, 13.68)

tad unnasam pāṇḍura dantam avraṇam |

śuci smitam padma palāśa locanam | drakṣye tad āryā vadanam kadā nv aham | prasanna tārā adhipa tulya darśanam ||

A killer smile, a sleek figure, an enchanting countenance - these things can be quite harmful to one who is trying to control their senses. One who is sober, or dhira, cannot be distracted from his assigned duties in life despite any impediment. Yet the man vying for supremacy in spiritual efforts, for overcoming the influence of the senses that have led him astray for far too long, can best be attacked by the sight of a beautiful woman, who can lure him into the depths of danger. In this respect, the eyes of the more renounced spiritualists steer clear of women, even if the women potentially being viewed pose no threat. In the spiritual world, however, such rules don’t apply. With the most beautiful woman, her vision is always appreciated, beneficial, and never harmful to one’s spiritual aspirations. The wise eagerly anticipate that meeting with her and take any and all risk to ensure that the successful outcome arrives before their very eyes, that they drink the sweet nectar that is the beautiful spiritual form of the Supreme Personality of Godhead’s eternal consort, Sita Devi.

One person saw her, however, and didn’t seem to gain any benefit. The king of Lanka during a particular period of time in the Treta Yuga took Sita way from the side of her husband through a nefarious plot. Sita is the energy of God, the purified form of it. She doesn’t know any other business except loving her husband. As a divine personality, she can grant benedictions to others, such as by expanding herself in the form of opulence and wealth, but these valuables have an ideal use. Just as a currency may be traded for goods and services in a specific country, the notes printed up by the goddess of fortune and distributed to those she favors are meant to be cashed in for service to her husband, the Supreme Lord Himself, who roamed the earth during Ravana’s time in the guise of a warrior prince named Rama. Not any ordinary prince mind you; this was the most beautiful and the handsomest man in the world, who also happened to be the most capable bow warrior. One person saw her, however, and didn’t seem to gain any benefit. The king of Lanka during a particular period of time in the Treta Yuga took Sita way from the side of her husband through a nefarious plot. Sita is the energy of God, the purified form of it. She doesn’t know any other business except loving her husband. As a divine personality, she can grant benedictions to others, such as by expanding herself in the form of opulence and wealth, but these valuables have an ideal use. Just as a currency may be traded for goods and services in a specific country, the notes printed up by the goddess of fortune and distributed to those she favors are meant to be cashed in for service to her husband, the Supreme Lord Himself, who roamed the earth during Ravana’s time in the guise of a warrior prince named Rama. Not any ordinary prince mind you; this was the most beautiful and the handsomest man in the world, who also happened to be the most capable bow warrior.

When the wonderful benedictions given by Sita Devi are used for other purposes, those that lack a relation to Rama’s pleasure, they can cause great harm to the person having temporary possession of them. Imagine having a car battery and installing it incorrectly in the car. There can be both sparks and an explosion when the battery is put in the wrong way. Imagine having scissors, a key, or some other metallic object and deciding to stick it into an electrical socket. These actions seem silly, but then so is taking the opulence provided by the goddess of fortune and using it for any purpose besides devotional service, the real occupational duty of the soul.

Ravana tried to use Sita Devi for his own pleasure. He didn’t have the courage to fight Rama one on one to win her hand. He knew from the words of Akampana, one of his fiendish contemporaries, that Rama would smoke him in battle in an instant. Therefore he approached Sita in a false guise and then forcefully took her back to his island kingdom of Lanka. He got to see her in person, marvel at her beauty, and personally give himself over to her. Yet she rejected him outright, as she has no desire to be with any man except Rama. Ravana was anxious to see Sita and he got his desire fulfilled. Yet his vision was clouded, and this flaw would cause him to act in the wrong way. When something is done improperly, there are negative consequences; otherwise where does the incorrectness come into play?

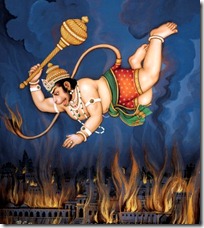

In Ravana’s case, the punishment would come in two stages. First there was the visit by Hanuman, Rama’s messenger. Lord Rama, the prince of Ayodhya and all-knowing Supreme Lord, could have found Sita Himself, but then what work would have been left for others? If one person in the company took on all the tasks, what would the other employees do? In the business environment, it’s difficult for one man to do everything, but we know by the wonders of this creation that the Supreme Lord can do whatever He wants. Through His energies the large land masses known as planets float in the air without any machine to prop them up. The material elements operate seemingly like clockwork, which is again instituted by the Supreme Lord and His energies. Therefore finding Sita would have been no problem for Rama. In Ravana’s case, the punishment would come in two stages. First there was the visit by Hanuman, Rama’s messenger. Lord Rama, the prince of Ayodhya and all-knowing Supreme Lord, could have found Sita Himself, but then what work would have been left for others? If one person in the company took on all the tasks, what would the other employees do? In the business environment, it’s difficult for one man to do everything, but we know by the wonders of this creation that the Supreme Lord can do whatever He wants. Through His energies the large land masses known as planets float in the air without any machine to prop them up. The material elements operate seemingly like clockwork, which is again instituted by the Supreme Lord and His energies. Therefore finding Sita would have been no problem for Rama.

Hanuman and the Vanaras residing in Kishkindha were very eager to please the Supreme Lord; so they were given opportunities for service. Hanuman was the most eager, so he was provided the most difficult task. One who can complete the toughest mission under very difficult conditions earns even more fame with their success. The obstacles faced by Hanuman were unimaginable, so much so that they tax the brain of the person who hears about them. He had to deal with people obstructing his path, the fact that the enemy territory was infested with ogres given to sinful behavior, and his own mental demons. Doubt can get the better of even the most confident person, especially when the time factor is considered. A person can be dexterous and resourceful, but if they start running out of time to finish their task, their abilities get neutralized. You can have the best quarterback in the world with the ball in his hands, but if there is little time left on the clock, there is not much he can do to help his team win.

Hanuman had to deal with the time factor in relation to Sita’s well-being. If she was in Lanka as had been previously learned, then surely Ravana was waiting to kill her. If Hanuman failed to find Sita, what would he tell his friends back home? How could he look Rama in the face? Hanuman had no reason to lament or be disappointed, for just getting to Lanka and searching the area unnoticed were amazing feats in their own right. But he is never focused on temporary accomplishments or patting himself on the back. The mission that would please Rama was not successfully complete yet, so that’s all he was worried about.

Finally, Hanuman decided to search the one place he hadn’t entered yet: a nearby Ashoka grove. Just prior to entering it, he offered prayers to Sita, Rama and Lakshmana, the Lord’s younger brother. He also asked the many divine figures in the heavenly realm to be favorable upon him. In the above referenced verse we see him asking the question to himself of when he will finally see Sita. He lists her specific qualities as a reminder of why she is so brilliant. He also reveals his eagerness to have the divine vision of such a wonderful person, who had no flaws whatsoever. Finally, Hanuman decided to search the one place he hadn’t entered yet: a nearby Ashoka grove. Just prior to entering it, he offered prayers to Sita, Rama and Lakshmana, the Lord’s younger brother. He also asked the many divine figures in the heavenly realm to be favorable upon him. In the above referenced verse we see him asking the question to himself of when he will finally see Sita. He lists her specific qualities as a reminder of why she is so brilliant. He also reveals his eagerness to have the divine vision of such a wonderful person, who had no flaws whatsoever.

Today, we know from Hanuman’s stature that his eagerness to see Sita, a beautiful woman even by the material estimation, was not harmful, but for Ravana it was. Ravana eventually lost everything because of his desire to see Sita, while Hanuman gained eternal fame and adoration from pious people looking to remain committed to the path of bhakti-yoga. In the Vedic tradition, it is emphatically stressed that a man should look upon every woman except his wife as his own mother. This way the urges for sex are curbed and the proper respect is given to females. Regardless of how the female behaves, whether she is married or unmarried, young or old, the same respectful treatment should be offered.

This guiding principle reveals the difference in outcomes. Hanuman saw Sita properly, even though he had never met her before. He eagerly anticipated being graced with the presence of Rama’s wife, but Hanuman had no desire to enjoy Sita in the way that Ravana did. Rather, anyone who sees the beautiful princess of Videha, the beloved daughter of Maharaja Janaka, and worships her in the proper mood can be granted only benedictions in life. Hanuman’s eagerness would pay off, as he would later beat down every opposing force that came his way.

In his initial meeting with Sita, whom he would finally find in the Ashoka wood almost emaciated due to the pain of separation from Rama, there would be some difficulties to overcome. Hanuman was so anxious to defeat Ravana and make Rama happy that he suggested to Sita that she come back to Kishkindha with him. Hearing this, Sita practically insulted Hanuman by saying that his monkey nature must have been coming out, for how could he suggest such a ridiculous thing like carrying her on his back? Hanuman felt a little hurt, but he did not get angry nor did his love for Sita diminish. Sita’s reservation related entirely to her love for Rama. She did not want to touch another man again. She was forced to by Ravana, but her vow was to always be devoted to Rama in every act. Moreover, she did not want her husband’s reputation sullied by the fact that someone else had to come and rescue His wife. In his initial meeting with Sita, whom he would finally find in the Ashoka wood almost emaciated due to the pain of separation from Rama, there would be some difficulties to overcome. Hanuman was so anxious to defeat Ravana and make Rama happy that he suggested to Sita that she come back to Kishkindha with him. Hearing this, Sita practically insulted Hanuman by saying that his monkey nature must have been coming out, for how could he suggest such a ridiculous thing like carrying her on his back? Hanuman felt a little hurt, but he did not get angry nor did his love for Sita diminish. Sita’s reservation related entirely to her love for Rama. She did not want to touch another man again. She was forced to by Ravana, but her vow was to always be devoted to Rama in every act. Moreover, she did not want her husband’s reputation sullied by the fact that someone else had to come and rescue His wife.

The admonition was harmless, and Sita would be so pleased by Hanuman and his bravery that she would shower him with so many gifts, benedictions that continue to arrive to this day. On his way out of Lanka to return to Rama, Hanuman would be bound up and have his tail set on fire by Ravana. While being paraded around the city in this way, Sita saw Hanuman and immediately prayed that the fire would feel as cool as ice for him. Of course who can ever deny the requests of Rama’s wife, who has more accumulated pious deeds than anyone else? Hanuman, not feeling the pain of the fire anymore, freed himself from the shackles and then proceeded to use his fiery tail to burn Lanka. This was how Ravana’s first punishment for having taken Sita arrived.

Ravana’s ultimate reward would be delivered by Rama Himself, who would shoot the arrows that would take his life. Thus Ravana’s lusty desires led to his eventual demise, whereas Hanuman’s pure desires relating to Sita brought him eternal fame. To this day, Sita ensures that Hanuman has whatever he needs to continue his devotional practices. He daily sings the glories of Sita and Rama, and we daily remember and honor Hanuman, who keeps the divine couple safely within his heart. He had the sight of Sita that he wanted so badly, and everything favorable came about in his life because of that eagerness. Anyone who is similarly eager to see Hanuman and remember his bravery, courage, honor, dedication to piety, and perseverance in pleasing Rama will meet with auspiciousness in both this life and the next.

In Closing:

Hanuman was full of eagerness,

To see Sita, she of face flawless.

Her countenance resembled the moon that is bright,

Lotus-petal eyes and white teeth made for brilliant sight.

Taking Sita, Ravana did something very unwise,

Through Hanuman and Rama, to find ultimate demise.

Hanuman had similar desire but it was pure,

So for benedictions he was assured.

Sita’s prayer to fix his burning tail,

Her gifts to devotees never fail.

|

Search This Blog

Thursday, April 19, 2012

A Flawless Face

The First Afghan war 1879 Photos Portraits, Amazing first Anglo-Afghan war Images Collection

The failure of the mission in 1837, the governor-general of India, Lord Auckland, the invasion of Afghanistan restore Shuja Shah, who ruled Afghanistan from 1803 to 1809 were the first Anglo-Afghan war, demonstrated the ease of a failure in Afghanistan and the difficulties to maintain. British and Indian army soldiers , at the end of December 1838, arrived in Quetta Marcio 1839th in late April, the British took Kandahar without a fight. In July, two months later, in Kandahar, the British attacked the fortress of Ghazni, some British troops returned to India, but it soon became clear that only the presence of British military control Shuji. Fire Jalalabad, Ghazni, Kandahar, Kalat iGhilzai (light), and Bamiyan.

Crime and punishment: The neurobiological roots of modern justice

A pair of neuroscientists from Vanderbilt and Harvard propose that five specific areas in the brain have been repurposed by evolution to enable third party punishment, which makes human prosociality possible. Credit: Rene Marois, Deborah Brewingtons / Vanderbilt University

A pair of neuroscientists from Vanderbilt and Harvard Universities have proposed the first neurobiological model for third-party punishment. It outlines a collection of potential cognitive and brain processes that evolutionary pressures could have re-purposed to make this behaviour possible.

The willingness of people to punish others who lie, cheat, steal or violate other social norms, even when they weren't harmed and don't stand to benefit personally, is distinctly human behaviour. There is scant evidence that other animals, even other primates, behave in this "I punish you because you harmed him" fashion. Although this behaviour – called third-party punishment – has long been institutionalized in human legal systems, and economists have identified it as one of the key factors that can explain the exceptional degree of cooperation that exists in human society, it is a new subject for neuroscience.

In a paper published online on April 15 by the journal Nature Neuroscience, a pair of neuroscientists from Vanderbilt and Harvard universities propose the first neurobiological model for third-party punishment. The model outlines a collection of potential cognitive and brain processes that evolutionary pressures could have repurposed to make this behavior possible.

"The concepts of survival of the fittest or the selfish gene that the public generally associates with evolution are incomplete," said René Marois, associate professor of psychology at Vanderbilt, who co-authored the paper with Joshua Buckholtz, assistant professor of psychology at Harvard. "Prosociality – voluntary behavior intended to benefit other people even when they are not kin – does not necessarily confer genetic benefits directly on specific individuals but it creates a stable society that improves the overall survival of the group's offspring."

One of the underlying mental abilities that allows humans to establish large-scale cooperation between genetically unrelated individuals is the capability to create, transmit and enforce social norms, widely shared sentiments about what constitutes appropriate behavior. These norms take a variety of forms, ranging from culturally specific standards of behavior (such as "thou shall greet an acquaintance of the opposite sex with a kiss on each cheek") to universal standards that vary in strength in different cultures (such as "thou shalt not commit adultery") to universal norms that are so widely held that that they are codified into laws (such as "thou shalt not kill").

"Scientists have advanced several models to explain the widespread cooperation that is characteristic of human society, but these generally fail to explain the emergence of our large stable societies" said Marois.

One model holds that individuals will perform altruistic actions when they benefit his or her kin and increase the likelihood of transmitting genes that they share to future generations. However, it doesn't explain why individuals cooperate with people who do not share their genes.

"You scratch my back and I'll scratch your back" is the essence of another model called reciprocal altruism or direct reciprocity. It argues that when two people interact repeatedly they have a mutual self-interest in cooperating. Although this can explain cooperation among unrelated people, scientists have found that it only works in relatively small groups.

Similarly, theories of indirect reciprocity, which focus on the benefits an individual gains by maintaining a good reputation through altruistic behavior, cannot account for the widespread emergence of cooperation because the benefits that individuals accrue through one-shot altruistic interactions are negligible.

There is one class of models, however, that has been successful in explaining the maintenance of cooperation among genetically unrelated individuals. According to these strong reciprocity models, individuals will reward norm-followers or punish norm-violators even at a cost to themselves (altruistic punishment).

Strong reciprocity models, like the other models mentioned above, have primarily been developed to account for second-party interactions. While second-party interactions may prevail in non-human primate and small human societies, there is evidence that the evolution of our large-scale societies hinged on a different, and more characteristically human form of interaction, namely third-party punishment ("I punish you because you harmed him").

The codification of social norms into laws and the institutionalization of third-party punishment "is arguably one of the most important developments in human culture," the paper states.

According to the researchers' model, which is based on the latest behavioral, cognitive and neuro-scientific data, third-party punishment grew out of second-party punishment and is implemented by a collection of cognitive processes that evolved to serve other functions but were co-opted to make third-party punishment possible.

In the modern criminal justice system, judges and jury members – impartial third-party decision-makers – are tasked to evaluate the severity of a criminal act, the mental state of the accused and the amount of harm done, and then integrate these evaluations with the applicable legal codes and select the most appropriate punishment from available options. Based on recent brain mapping studies, Buckholtz and Marois propose a cascade of brain events that take place to support the cognitive processes involved in third-party punishment decision-making. Specifically, they have localized these processes to five distinct areas in the brain – two in the frontal cortex, which is involved in higher mental functions; the amygdala deep in the brain that is associated with emotional responses; and two areas in the back of the brain that are involved in social evaluation and response selection.

According to Buckholtz and Marois' model, punishment decisions are preceded by the evaluation of the actions and mental intentions of the criminal defendant in a social evaluation network comprised of the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ).

While it is often assumed that legal decision-making is purely based on rational thinking, research suggests that much of the motivation for punishing is driven by negative emotional responses to the harm. This signal appears to be generated in the amygdala, causing people to factor in their emotional state when making decisions instead of making solely factual judgments.

Next, the decision-maker must integrate his or her evaluation of the norm-violator's mental state and the amount of harm with the specific set of punishment options. The researchers propose that the medial prefrontal cortex, which is centrally located and has connections to all the other key areas, acts as a hub that brings all this information together and passes it to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), where the final decision is made with the input from another rear-brain area called the intraparietal sulcus, involved in selecting the appropriate punishment response. As such, the DLPFC may be at the apex of the neural hierarchy involved in deciding on the appropriate punishments that should be given to specific norm violations.

The current model focuses on the role of punishment in encouraging large-scale human cooperation, but the researchers recognize that reward and positive reinforcement are also powerful psychological forces that encourage both short-term and long-term cooperation.

Marois adds: "It is somewhat ironic that while punishment, or the threat of punishment, is thought to play a foundational role in the evolution of our large-scale societies, much research in developmental psychology demonstrates the immense power of positive reinforcement in shaping a young individual's behavior." Understanding how both reward and punishment work should therefore provide fundamental insights into the nature of human cooperative behavior. "The ultimate 'pot of gold at the end of the rainbow' here is to promote a criminal justice system that is not only fairer, but also less necessary," said Marois.

This work is the latest contribution of Vanderbilt researchers to the newly emerging field of neurolaw and was supported by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience, directed by Owen Jones, New York Alumni Chancellor's Chair in Law and professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt.

Provided by Vanderbilt University

"Crime and punishment: The neurobiological roots of modern justice." April 18th, 2012. http://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-04-crime-neurobiological-roots-modern-justice.html

Posted by

Robert Karl Stonjek

Robert Karl Stonjek

New study sheds light on how selective hearing works in the brain

Psychologists have known for decades about the so-called "cocktail party effect," a name that evokes the Mad Men era in which it was coined. It is the remarkable human ability to focus on a single speaker in virtually any environment—a classroom, sporting event or coffee bar—even if that person's voice is seemingly drowned out by a jabbering crowd.

To understand how selective hearing works in the brain, UCSF neurosurgeon Edward Chang, MD, a faculty member in the UCSF Department of Neurological Surgery and the Keck Center for Integrative Neuroscience, and UCSF postdoctoral fellow Nima Mesgarani, PhD, worked with three patients who were undergoing brain surgery for severe epilepsy.

Part of this surgery involves pinpointing the parts of the brain responsible for disabling seizures. The UCSF epilepsy team finds those locales by mapping the brain's activity over a week, with a thin sheet of up to 256 electrodes placed under the skull on the brain's outer surface or cortex. These electrodes record activity in the temporal lobe—home to the auditory cortex.

UCSF is one of few leading academic epilepsy centers where these advanced intracranial recordings are done, and, Chang said, the ability to safely record from the brain itself provides unique opportunities to advance our fundamental knowledge of how the brain works.

"The combination of high-resolution brain recordings and powerful decoding algorithms opens a window into the subjective experience of the mind that we've never seen before," Chang said.

In the experiments, patients listened to two speech samples played to them simultaneously in which different phrases were spoken by different speakers. They were asked to identify the words they heard spoken by one of the two speakers.

The authors then applied new decoding methods to "reconstruct" what the subjects heard from analyzing their brain activity patterns. Strikingly, the authors found that neural responses in the auditory cortex only reflected those of the targeted speaker. They found that their decoding algorithm could predict which speaker and even what specific words the subject was listening to based on those neural patterns. In other words, they could tell when the listener's attention strayed to another speaker.

"The algorithm worked so well that we could predict not only the correct responses, but also even when they paid attention to the wrong word," Chang said.

SPEECH RECOGNITION BY THE HUMAN BRAIN AND MACHINES

The new findings show that the representation of speech in the cortex does not just reflect the entire external acoustic environment but instead just what we really want or need to hear.

They represent a major advance in understanding how the human brain processes language, with immediate implications for the study of impairment during aging, attention deficit disorder, autism and language learning disorders.

In addition, Chang, who is also co-director of the Center for Neural Engineering and Prostheses at UC Berkeley and UCSF, said that we may someday be able to use this technology for neuroprosthetic devices for decoding the intentions and thoughts from paralyzed patients that cannot communicate.

Revealing how our brains are wired to favor some auditory cues over others may even inspire new approaches toward automating and improving how voice-activated electronic interfaces filter sounds in order to properly detect verbal commands.

How the brain can so effectively focus on a single voice is a problem of keen interest to the companies that make consumer technologies because of the tremendous future market for all kinds of electronic devices with voice-active interfaces. While the voice recognition technologies that enable such interfaces as Apple's Siri have come a long way in the last few years, they are nowhere near as sophisticated as the human speech system.

An average person can walk into a noisy room and have a private conversation with relative ease—as if all the other voices in the room were muted. In fact, said Mesgarani, an engineer with a background in automatic speech recognition research, the engineering required to separate a single intelligible voice from a cacophony of speakers and background noise is a surprisingly difficult problem.

Speech recognition, he said, is "something that humans are remarkably good at, but it turns out that machine emulation of this human ability is extremely difficult."

More information: The article, "Selective cortical representation of attended speaker in multi-talker speech perception" by Nima Mesgarani and Edward F. Chang appears in the April 19, 2012 issue of the journal Nature. http://dx.doi.org/ … /nature11020

Provided by University of California, San Francisco

"New study sheds light on how selective hearing works in the brain." April 18th, 2012. http://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-04-brain_1.html

Posted by

Robert Karl Stonjek

Robert Karl Stonjek

Killing in war linked with suicidal thoughts among Vietnam veterans, study finds

The experience of killing in war was strongly associated with thoughts of suicide, in a study of Vietnam-era veterans led by researchers at the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

The scientists found that veterans with more experiences involving killing were twice as likely to have reported suicidal thoughts as veterans who had fewer or no experiences.

To evaluate the experience of killing, the authors created four variables – killing enemy combatants, killing prisoners, killing civilians in general and killing or injuring women, children or the elderly. For each veteran, they combined those variables into a single composite measure. The higher the composite score, the greater the likelihood that a veteran had thought about suicide.

The relationship between killing and suicidal thoughts held even after the scientists adjusted for variables including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance use disorders and exposure to combat.

The study, which was published electronically on April 13 in the journal Depression and Anxiety, was based on an analysis of data from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Survey, a comprehensive study of a nationally representative sample of Vietnam-era veterans.

The authors cited other research indicating that veterans are at elevated risk of suicide compared to people with no military service. They noted that by 2009, the suicide rate in the U.S. Army had risen to 21.8 per 100,000 soldiers, a rate exceeding that of the general population.

"The VA has a lot of very good mental health programs, including programs targeting suicide prevention. Our goal is to make those programs even stronger," said lead author Shira Maguen, a clinical psychologist at SFVAMC and an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at UCSF. "We want clinicians and suicide prevention coordinators to be aware that in analyzing a veteran's risk of suicide, killing in combat is an additional factor that they may or may not be aware of."

Notably, the scientists found that the only variable with a significant link to actual suicide attempts among the veterans was PTSD – a finding that replicated earlier studies, according to Maguen. Thus, she said, the link between killing and suicide attempts was not as significant as the link between killing and suicidal thoughts.

Maguen noted that, currently, the mental health impact of killing is not formally evaluated as part of VA or Department of Defense mental health treatments, nor typically taken into consideration when assessing a veteran's risk of suicide.

"We know from our previous research how hard it is to talk about killing," Maguen cautioned. "It's important that we as care providers have these conversations with veterans in a supportive, therapeutic environment so that they will feel comfortable talking about their experiences."

The overall goal, she said, "is to look back and understand some lessons of the past that we can apply to the present. Talking with people who have had suicidal thoughts can potentially give us insights into why suicides occur, and hopefully help us prevent them."

Provided by University of California, San Francisco

"Killing in war linked with suicidal thoughts among Vietnam veterans, study finds." April 18th, 2012. http://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-04-war-linked-suicidal-thoughts-vietnam.html

Posted by

Robert Karl Stonjek

Robert Karl Stonjek

Opium use linked to almost double the risk of death from any cause

Long term opium use, even in relatively low doses, is associated with almost double the risk of death from many causes, particularly circulatory diseases, respiratory conditions and cancer, concludes a study published in the British Medical Journaltoday.

The findings remind us not only that opium is harmful, but raise questions about the risks of long term prescription opioids for treatment of chronic pain.

The research was carried out in northern Iran, where opium consumption is exceptionally common, and is the first study to measure the risks of death in opium users compared with non-users.

Around 20 million people worldwide use opium or its derivatives. Studies suggest a possible role of opium in throat cancer, bladder cancer, coronary heart disease and a few other conditions, but little is known about its effect on overall mortality, particularly for low-dose opium used over a long period

So an international research team set out to investigate the association between opium use and subsequent risk of death.

They studied opium use among 50,045 men and women aged 40 to 75 years living in Golestan Province in northern Iran for an average of five years.

A total of 17% (8,487) participants reported opium use, with an average duration of 12.7 years. 2,145 deaths were reported during the study period.

After adjusting for several factors including poverty and cigarette smoking, opium use was associated with an 86% increased risk of deaths from several major causes including circulatory diseases, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tuberculosis and cancer.

Even after excluding those who self-prescribed opium after the onset of a chronic illness, the associations remained strong and a dose-response relationship was seen.

Increased mortality was seen for different types of opium. Both opium ingestion and opium smoking were associated with a higher risk of death.

Assuming this represents a direct (causal) association, the authors estimate that 15% of all deaths in this population are attributable to opium. They call for more studies on opium use and mortality and of patients taking long term opioid analgesics for treatment of pain to help shed further light on this issue.

"In a linked editorial, Assistant Professor Irfan Dhalla from St Michael's Hospital in Toronto says that in high income countries doctors rarely, if ever, encounter someone who uses opium. However he warns that millions of patients with chronic pain are prescribed opioids such as morphine and codeine that may carry "risks that are incompletely understood."

More information: http://www.bmj.com … 36/bmj.e2502

Provided by British Medical Journal

"Opium use linked to almost double the risk of death from any cause." April 17th, 2012. http://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-04-opium-linked-death.html

Posted by

Robert Karl Stonjek

Robert Karl Stonjek

Curbing college binge drinking: What role do 'alcohol expectancies' play?

Researchers at The Miriam Hospital say interventions targeting what college students often see as the pleasurable effects of alcohol – including loosened inhibitions and feeling more bold and outgoing – may be one way to stem the tide of dangerous and widespread binge drinking on college campuses.

According to a new report, "alcohol expectancy challenges," or social experiments aimed at challenging students' beliefs about the rewards of drinking, can successfully reduce both the quantity of alcohol consumed and the frequency of heavy or binge drinking among college students.

The findings are published online by the Psychology of Addictive Behaviors.

"We know drinking habits can be influenced by what people expect will happen when they consume alcohol, so if you believe alcohol gives you 'liquid courage' or that drinking helps you 'fit in' or be more social, you're likely to drink more," said the study's lead author, Lori A.J. Scott-Sheldon, Ph.D., of The Miriam Hospital's Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine

"If we can prove to students that many of the perceived positive side effects of alcohol are actually due to their expectations, rather than the alcohol itself, then we could potentially reduce frequent binge drinking and its negative consequences," she added.

Drinking is pervasive on most college campuses in the United States. Data from several national surveys indicate that about four in five college students drink and that about half of college student drinkers engage in heavy episodic consumption. Excessive alcohol use is associated with a number of short- and long-term consequences, including academic problems, sexual assault, unsafe sex, injuries and violence, arrests, college attrition, alcohol abuse and dependence, and accidental death. As a result, reducing alcohol consumption by college students has been declared a public health priority by the Surgeon General.

Alcohol expectancy challenges have been designated by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as one of only three effective alcohol-prevention treatments for college students. During a typical expectancy challenge intervention, alcohol is provided to a group in a bar-like setting; some drinks contain alcohol while others are non-alcoholic, but the participants do not know which type of beverage they have. Students then engage in activities that promote social interaction, such as party games, and after some time, they are asked to evaluate whether other participants were drinking alcohol versus a placebo. In the majority of cases, groups had difficulty determining who actually received alcohol and who did not.

The challenge also offers an opportunity to educate college drinkers about alcohol expectancies, myths about the effects of alcohol, the pharmacology of alcohol and drinking responsibly.

Scott-Sheldon and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 19 separate alcohol expectancy challenges among more than 1,400 college students across the country. Overall, participants reported lower positive alcohol expectancies and reduced both their alcohol use and their frequency of heavy drinking for as long as one month post-intervention.

In most cases, expectancy challenge interventions were delivered in three or fewer group sessions. Because it may not require as many resources as the more individualized strategies that are commonly used for college drinkers, Scott-Sheldon says colleges may find this approach a more attractive alternative.

"This relatively brief, group-based intervention is something that could be easily implemented within the context of campus group activities, such as the residence life program, student orientation or student organization events," she said.

Because the effects of alcohol expectancy challenges are brief, researchers say providers might consider implementing these interventions before periods when students are more likely to engage in at-risk drinking behavior, such as spring break or "rush week" for fraternities or sororities.

Provided by Lifespan

"Curbing college binge drinking: What role do 'alcohol expectancies' play?." April 18th, 2012. http://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-04-curbing-college-binge-role-alcohol.html

Posted by

Robert Karl Stonjek

Robert Karl Stonjek

Good to read

People come into your life for a reason, a season or a lifetime.

When you know which one it is, you will know what to do for that

Person...

When someone is in your life for a REASON, it is usually to meet a need

You have expressed.

They have come to assist you through a difficulty, to provide you with

Guidance and support,

To aid you physically, emotionally or spiritually.

They may seem like a godsend and they are.

They are there for the reason you need them to be.

Then, without any wrongdoing on your part or at an inconvenient time,

This person will say or do something to bring the relationship to an

End.

Sometimes they die. Sometimes they walk away.

Sometimes they act up and force you to take a stand.

What we must realize is that our need has been met, our desire

Fulfilled, their work is done.

The prayer you sent up has been answered and now it is time to move on.

Some people come into your life for a SEASON, because your turn has

Come to share, grow or learn.

They bring you an experience of peace or make you laugh.

They may teach you something you have never done.

They usually give you an unbelievable amount of joy..

Believe it, it is real.. But only for a season.

LIFETIME relationships teach you lifetime lessons,

Things you must build upon in order to have a solid emotional

Foundation..

Your job is to accept the lesson,

Love the person and put what you have learned to use in all other

Relationships and areas of your life.

It is said that love is blind but friendship is clairvoyant.

Thank you for being a part of my life,

Whether you were a reason, a season or a lifetime.

Gene hunt is on for mental disability

Pioneering clinical genome-sequencing projects focus on patients with developmental delay.

Ewen Callaway

Han Brunner

Medical geneticists are giving genome sequencing its first big test in the clinic by applying it to some of their most baffling cases. By the end of this year, hundreds of children with unexplained forms of intellectual disability and developmental delay will have had their genomes decoded as part of the first large-scale, national clinical sequencing projects.

These programmes, which were discussed last month at a rare-diseases conference hosted by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute near Cambridge, UK, aim to provide a genetic diagnosis that could end years of uncertainty about a child’s disability. In the longer term, they could provide crucial data that will underpin efforts to develop therapies. The projects are also highlighting the logistical and ethical challenges of bringing genome sequencing to the consulting room. “The overarching theme is that genome-based diagnosis is now hitting mainstream medicine,” says Han Brunner, a medical geneticist at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in the Netherlands, who leads one of the projects.

About 2% of children experience some form of intellectual disability. Many have disorders such as Down’s syndrome and fragile X syndrome, which are linked to known genetic abnormalities and so are easily diagnosed. Others have experienced environmental risk factors, such as fetal alcohol exposure, that rule out a simple genetic explanation. However, a large proportion of intellectual disability cases are thought to be the work of single, as-yet-unidentified mutations.

Scientists estimate that about 1,000 genes are involved in the function of the healthy brain. “There are so many genes that can go wrong and give you intellectual disability,” says André Reis, a medical geneticist at Erlangen University Hospital in Germany. Reis’s group, the German Mental Retardation Network, has already sequenced the exomes — the 1–2% of the genome that contains instructions for building proteins — of about 50 patients with severe intellectual disability.

Joining the hunt is a UK-based programme called Deciphering Developmental Disorders, which expects to sequence 1,000 exomes by the year’s end, with an ultimate goal of diagnosing up to 12,000 British children with developmental delay. A Canadian project called FORGE (finding of rare disease genes) aims to sequence children and families with 200 different disorders this year. And in the United States, the National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, recently funded three Mendelian Disorders Sequencing Centers that will apply genome sequencing to diagnosing thousands of patients with a wider range of rare diseases, including intellectual disability and developmental delay.

First glance

Early results are coming in from Brunner’s team, which has already sequenced about 100 exomes of children with intellectual disability. By comparing the children’s exomes with those of the parents, the researchers have identified new mutations — potential causes of the disorder — in as many as 40% of the cases. The other programmes are having similar success at making possible genetic diagnoses.

In most cases, identifying mutations will not point to medical treatments, let alone cures. But scientists say the importance of a diagnosis should not be discounted. “Parents have been struggling with the delay of their children for years. They have gone from one doctor to the next, had all kinds of tests done on their children looking for an explanation,” Reis says. Knowing that the mutation causing a child’s intellectual disability is new rather than inherited can also reassure parents that other children they conceive are unlikely to have the same disease.

Treatments could eventually follow. The projects are guiding research in mice, zebrafish and fruitflies, with the goal of unpicking the mechanisms of mental disorders. But it will undoubtedly be a long time before any potential therapies are tried in humans: an early-stage clinical trial of a drug to treat fragile X syndrome, for example, was published last year (S. Jacquemont et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 64ra1; 2011), some two decades after the gene underlying the condition, FMR1, was identified.

The work is also throwing up a fresh challenge: how can scientists be sure that a specific mutation is the cause of a particular form of mental disability? “It’s not clear what is the threshold of evidence at which you can say this is the causal variant in this patient,” says Daniel MacArthur, a geneticist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. In a recent Science paper, his team estimated that the average healthy genome contains about 100 gene-disabling mutations. Such ‘background noise’ could lead scientists astray in their hunt for causal mutations.

Brunner says that about half of the mutations his team has identified have previously been seen in other patients with similar forms of intellectual disability, offering enough assurance to make a diagnosis. Circumstantial evidence, such as indications that the mutation disrupts a gene expressed in the brains of animals, ties the other half of the mutations to intellectual disability. But making a solid case often requires identifying second, third and fourth patients with similar mutations and symptoms.

Scientists are already forging these connections on an informal basis. At the Sanger Institute meeting, several groups reported mutations in a gene called ARID1B in patients with intellectual disability. James Lupski, a medical geneticist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, says that when his team identifies a potentially disease-causing mutation in a patient genome, he e-mails other scientists to see whether they have found similar mutations.

But researchers agree that they need a more formalized way to make these connections. To that end, the US National Center for Biotechnology Information in Bethesda is developing a database, ClinVar, to integrate clinical and genetic data; others, such as DECIPHER, run by the Sanger Institute, handle genetic data such as chromosome rearrangements that can disrupt genes.

The first clinical sequencing projects are also grappling with what they should or shouldn’t tell patients. “We don’t want people coming into our clinic for intellectual disability and coming out with a cancer gene; this is not what they came for,” says Reis.

Brunner’s team once had to face just that situation. The researchers identified a mutation in a gene in one patient that could increase the risk of colon cancer as an adult. The project’s ethical review board had determined that if families wanted to know of mutations potentially underlying a child’s intellectual disability, they must also be willing to receive such incidental findings, and so the child’s parents were told. But clinical sequencing projects vary in their approach to incidental results. For the time being, Deciphering Developmental Disorders will not inform families about such findings. For FORGE Canada, the policy varies from province to province.

A working group convened by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics in Bethesda recently suggested drawing up a list of gene mutations that ought to be routinely reported back to patients. The list would include mutations strongly linked to conditions for which a medical intervention is available.

“This is a fast-changing ethical environment,” says Matt Hurles, a geneticist at the Sanger Institute and one of the leaders of Deciphering Developmental Disorders. His team is conducting a web-based survey to gauge the attitudes of parents, physicians and the general public towards disclosing incidental genomic findings. Lupski admits, “We’re learning as we go along. People don’t want to hear that, but that’s the truth of the matter.”

Scientists and clinicians hope that the lessons learned in these initial large-scale clinical sequencing projects will inform genomic medicine as it reaches more patients and moves to other specialities, such as neurology and cardiology, and even to routine health care. “If in five years time this project hasn’t catalysed the adoption of genomic technologies which have been shown to be useful, in some degree we will have failed,” says Hurles.

Nature 484, 302–303

( 19 April 2012 )

doi :10.1038/484302a

Posted by

Robert Karl Stonjek

Robert Karl Stonjek

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)