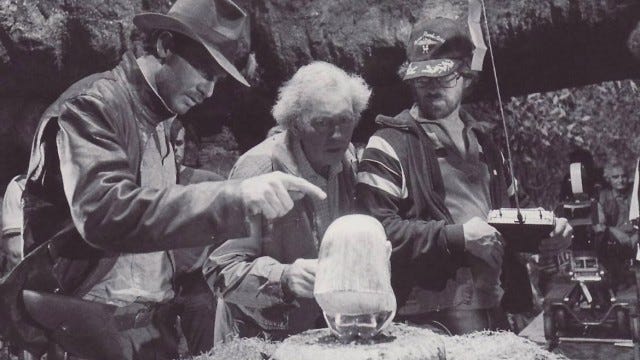

With a giant pile of movies to his name, Steven Spielberg has the considerable honor of being the only filmmaker who makes entertainment that’s massively popular, critically acclaimed and decade-enduring. It’s an illusive triumvirate. His fundamental success is owed to a lot of things, but principle among them is his childhood sense of wonder and magic — a sense he’s never let go of.

His childhood was also spent with a camera in hand.

From Jaws to Close Encounters of the Third Kind to Indiana Jones to The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun and Jurassic Park and Amistad and Schindler’s List and Munich and, and, and…he’s been a prolific, skilled presence in the filmmaking world for going on 5 decades, and he’s done so by spanning genres, tones, and subjects.

So here’s a bit of free film school (for fans and filmmakers alike) from a little kid who hid under his bed after watching Bambi.

Your Assumptions About Your Own Film Will Be Wrong

An excellent place to start. Perhaps the best singular piece of advice this column has looked at because it throws out a vile mindset that can corrode the filmmaking process. It’s easy to assume that as director (or producer) that you’ll have complete control over what you’re making. That assumption would be wrong.

“Well, for one thing, I don’t know what I’m in for. Most of my presumptions about a production are usually wrong. For instance, with Schindler’s List, I was pretty certain that whatever came my way in Poland I could tolerate, and just put my camera between myself and the subject, and protect myself, you know, by creating my own aesthetic distance. And immediately, on the first day of shooting, that broke down. I didn’t have that as a safety net, and immediately I realized that this was about to become the most personal professional experience of my life. It was a devastatingly insightful experience, but it’s something I still haven’t gotten over.

I think back on the production of Schindler’s List with very sad memories, because of the subject matter, not because of the working experience. The working experience was nearly perfect, because everybody held on to each other in that production. We formed a circle. It was very therapeutic, and for a lot of people, it changed their lives. A lot of the actors, a lot of the crew, it changed their lives. It changed my life, for sure. But then other productions that I’ve gone into with a blithe spirit, thinking, This film’s a pushover. It’s often when I take that attitude, the movie turns around and runs me over as if it were a tank. And so I’ve tried my best to stop second-guessing what the working experience is going to be like. Because I’m usually wrong.”

It might be the experience that can’t be predicted, but for anyone who’s ever tried to make a creature feature starring a shark only to make a Hitchcockian thriller about a shark that features almost no shark, it’s clear that the process can shift out from underneath you for reasons beyond your control. How you respond is what will define you and the movie.

The Right Kind of Collaboration is Key

“When I was a kid, there was no collaboration, it’s you with a camera bossing your friends around. But as an adult, filmmaking is all about appreciating the talents of the people you surround yourself with and knowing you could never have made any of these films by yourself.”

Movies are a team sport.

Be Your Perfect Audience (and Hold Onto Your Childhood)

A Little Scamming Never Hurt

“I was fifteen, or sixteen. I was in high school. I was spending a summer in California with my second cousins. And I wanted to be a director really bad. I was making a lot of 8mm home movies, since I was twelve, making little dramas and comedies with the neighborhood kids.

One day I decided to get on the Universal lot. I dressed up in a coat and tie. I actually had taken the tour the day before at Universal, and actually jumped off the tour bus. (It was a bus in those days.) I spent the whole day on the lot. Met a nice man named Chuck Silvers. Told him I was a filmmaker from Arizona.

He said, “Kid, come back tomorrow. I’ll write you a pass and you can show me some of your 8mm films.”

I had a little film festival for him.

He said, “You’re great. I hope you make it. But, because I’m just a librarian I can’t write you anymore passes.” (He laughs.)

So the next day, having observed how people dressed in those days, I dressed like them, carried a briefcase, and walked past the same guard, Scotty — who had been there for like a long time, because he the oldest. He waved me in.

For three months, that whole summer vacation, I came on the lot every single day. Found an office. Went to a little store that sold cameras and also plastic title letters to title your films. Got the letters. Found an abandoned office, and put my name and the number of my office on this directory. Opened up the glass directory and stuck these stick-on letters on the directory. And basically went into business for myself. But it never amounted to anything. I learned a lot about editing and dubbing by watching all the professionals do it, but I never got a job out of my imposition.”

Spielberg has spoken quite a few times about his Universal Studios scam as a young man, but it’s even more fascinating in the context of Catch Me If You Can.

Of course, you might not be able to pull off quite the same scam today.

More Isn’t Always More

“Bloated budgets are ruining Hollywood — these pictures are squeezing all the other types of movies out of Hollywood. It’s disastrous. When I made The Lost World I limited the amount of special-effects shots because they were incredibly expensive. If a dinosaur walks around, it costs $80,000 for eight seconds. If four dinosaurs are in the background, it’s $150,000. More doesn’t always make things better.”

Amen.

The Stress and Madness Might Be Worth It

“It was worth it because, for number one, Close Encounters, which was a film I had written and a film nobody seemed to want to make, everybody seemed to want it right after Jaws was a hit. So, the first thing Jaws did for me was it allowed a studio, namely Columbia, to greenlight Close Encounters. For number two, it gave me final cut for the rest of my career. But what I really owe to Jaws was creating in me a great deal of humility, about tempering my imagination with just sort of the facts of life.”

In the best interview Spielberg’s done, Quint from Aint It Cool spoke to him in considerable depth about his career and the crappy shark that changed it forever. He speaks on giving personality to special effects, his personal drive, and a dozen other topics. It’s a revealing talk, but one of the clear indications is that going through hell is sometimes necessary, but the rewards are also worth it.

What Have We Learned

Spielberg is a unique filmmaker in his ability to tell uncynical stories. As Richard Dreyfuss points out, there’s a positivity surrounding much of his work. A “niceness” that encompasses the tone and the aesthetic. There’s also a grand sense of adventure, and doesn’t that always stand in for a theme of human achievement? Of human possibility?

That’s what many of his films represent (even when the morality or pragmatism of that advancement is questioned), but on a simpler note, Spielberg succeeds because he’s able to make jaws drop. Sometimes it’s because of human cruelty/kindness, a terrifying nightmare, or because a huge valley is filled with living dinosaurs.

Dropped jaws are at the heart of his filmmaking, and at the heart of that sensation is a spark of wonder that the younger versions of us understand better than we do. Spielberg stands hand in hand with his younger self, making magic

thanks https://filmschoolrejects.com

thanks https://filmschoolrejects.com

No comments:

Post a Comment